Lizard … Bad Guy or Superhero?

Lizard … Bad Guy or Superhero?

When I started this Treasure Hunt, I began by thinking about whether lizards, like snakes, conjure up negative images and feelings. After some research, I  decided that the only reason I even thought about this issue was the expression “Lounge Lizard”; originally coined by the Flappers of the 1920s and used to describe men who hung around bars trying to pick up women … preferably rich ones. Apparently, the term has resurfaced every decade during the past 100 years and is still in use. With this flimsy negative evidence, and what follows, you decide whether the Western Fence Lizard may qualify as a Superhero.

decided that the only reason I even thought about this issue was the expression “Lounge Lizard”; originally coined by the Flappers of the 1920s and used to describe men who hung around bars trying to pick up women … preferably rich ones. Apparently, the term has resurfaced every decade during the past 100 years and is still in use. With this flimsy negative evidence, and what follows, you decide whether the Western Fence Lizard may qualify as a Superhero.

Western Fence Lizards Found All Over California

Of the three common lizards found on More Mesa, the Western Fence Lizard, also called Bluebelly, is a fairly well-known and recognized reptile. And it also seems to have captured the imagination of many northern California residents, as I found some of the most interesting information on this animal in Bay area publications.

Of the three common lizards found on More Mesa, the Western Fence Lizard, also called Bluebelly, is a fairly well-known and recognized reptile. And it also seems to have captured the imagination of many northern California residents, as I found some of the most interesting information on this animal in Bay area publications.

Although it occurs in small numbers throughout many western states, California is definitely home territory for the Western Fence Lizard, where we host six separate subspecies; among them the Central Coast’s “Great Basin Fence Lizard”. Moreover, the Channel Islands are the only place on the planet you will find the “Islands Fence Lizard.” (You may remember that the Gopher Snake also had a subspecies found only on the Channel Islands, and we also talked about these remarkable islands in our issue on Western Gulls. Try to get out there if you can. It’s an amazing place, and it is in our very own back yard!)

Cunning Little Blue Guy

Western Fence Lizards are brown to black in color with black stripes on their backs. However, their most distinguishing feature is their bright blue bellies and throat patches. Characteristically, as happens in most of the animal and bird kingdoms, the males have to “dress up” whereas the females and juveniles have faint or no color … very drab indeed! The bodies of these little guys measure 2 ¼-3 ½ inches with a total length (including tail) of about 8 inches. Why do we care about measurements with and without the tail? As it turns out, the Western Fence Lizard has a surprise in store for potential enemies chasing it down. When they get too close, the lizard contracts muscles at weak spots in its tail. Then nerves, blood vessels and muscles break, the tail is left in the mouth of the predator and the lizard makes a very hasty exit. While the predator is confusedly trying to figure out what just happened, the lizard begins growing a new tail.

The “quick release” tail is not the only weapon in the Western Fence Lizard’s arsenal against predators. They are very fast, very skittish, have excellent reflexes and can bite, or even poop on predators as well.

Life Cycle Includes All Regular Activities … and Brumation

Cold-blooded Western Fence Lizards lead a solitary life. They are diurnal reptiles and are commonly seen sunning on paths, rocks, and fence posts, and other high places, which sometimes makes them easy prey for birds and even some mammals. The lizard itself is a carnivore, eating worms of all kinds, caterpillars, spiders, mosquitoes, grasshoppers, beetles, crickets, flies, ants and ticks. (Ticks are a “big deal” as you will see below.) Like snakes, lizards molt so that they have a new skin, as well as a new tail … as needed.

And in the procreation department …

Stimulated by an increase in day length, Western Fence Lizards mate in the spring or early summer, and do not breed until the spring of their second

Stimulated by an increase in day length, Western Fence Lizards mate in the spring or early summer, and do not breed until the spring of their second

year. It is at this time of year that one is likely to observe the characteristic “push-ups” that many lizards exhibit. Females will lay one to three clutches of three or more eggs (usually eight) between April and July. During the mating season, adult males will defend a home range. The eggs hatch in August. (We should also note that push-ups have other purposes, besides the courtship ritual. They can also be used for domination effect or claiming territory.)

Sleepy Time … Lizards are cold-blooded and do best with daytime temperature between 75-85 degrees F and nighttime temperatures around 62 degrees F. This means that they need to do something akin to hibernation during the winter. What they do is not true hibernation, but a cold-blooded version of slowing down that is called “brumation”; a state or condition of sluggishness, inactivity, or torpor exhibited by reptiles during winter or extended periods of low temperatures.

The average life of a Pacific Fence Lizard is relatively short in a natural setting. Up to 80% of the lizard population may die each year. However, they have the potential to live up to five years under optimal conditions.

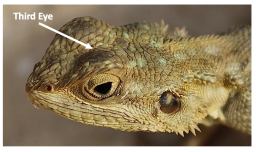

A Third Eye?

Remember the Treasure Hunt about Bees? Bees have five eyes; three little ones at the top of their heads to help with navigation and stability, and two huge, compound eyes to give them all the information they need to understand their environment. As it turns out, many lizards have one additional eye, much smaller than their two “regular” eyes. This third eye is located at the midline of the top of their heads. It is formally known as a “parietal eye” and is hard to see because it is usually covered by a thick, large scale. While the third eye is less developed than the regular eyes, it does have a cornea, a lens and a retina … but no rods or cones … and does not form an image.

So why do they need a third eye? The only job of the third eye is to differentiate between light and dark. And while that seems unimportant to us as warm-blooded mammals, reptiles are cold-blooded and need more specific information than we do for certain phenomena. Research has shown the third eye acts as a calendar of sorts. It sees days getting longer and nights getting shorter and the reverse; thereby transmitting to the reptile brain how the seasons are changing. This information is critical to maintaining body temperature and daily circadian rhythms, and ends up acting as a monitor of most lizard life cycles such as sleep and reproduction

Super Hero Disease Fighter … or Not?

Lyme Disease, identified in the mid 1970s, is the most commonly reported vector-borne disease in the United States. It affects about 300,000 people each year, mostly in the Northeast. One contracts this disease from a bite by a Black Legged (Deer) Tick. A little over 20 years ago, I began following the Lyme Disease saga. At that time, a Berkeley researcher presented evidence that the ticks he  pulled off Western Fence Lizards … and there are a lot of ticks on the lizards … never seemed to carry Lyme. His conclusion was that the lizard’s blood had unique proteins that killed off the bacterium. Since the incidence of Lyme in California was markedly lower that incidence in the Northeast, where there are no Fence Lizards, the difference was awarded to the tiny Fence Lizard and it became a Super Hero.

pulled off Western Fence Lizards … and there are a lot of ticks on the lizards … never seemed to carry Lyme. His conclusion was that the lizard’s blood had unique proteins that killed off the bacterium. Since the incidence of Lyme in California was markedly lower that incidence in the Northeast, where there are no Fence Lizards, the difference was awarded to the tiny Fence Lizard and it became a Super Hero.

I was taking a rigorous statistics course at the time and did a paper that I hoped would shed some light on the issue. One of the things I looked at was humidity … the ticks like it, there is lots of it in the Northeast, we don’t have much of it in Southern California and there is more of it in Northern California … where there is more Lyme than in Southern California. However, there was insufficient evidence to draw any credible conclusions. And, you will find that, to this day, most articles on Lyme and Fence Lizards still reference the early work and credit the lizards as heroic defenders of California from Lyme Disease.

But, as with all things in nature, it’s COMPLICATED! A new research study removed all the Fence Lizards from an area in Northern California and the incidence of Lyme’s went down!

What really is happening, and why, exactly, does the Northeast have 226 times more Lyme cases than we do in California? According to a recent article in Bay Nature

What really is happening, and why, exactly, does the Northeast have 226 times more Lyme cases than we do in California? According to a recent article in Bay Nature

Magazine it could be lots of things. For example, overall weather; i.e.seasonality, humidity, dry spells. And, get ready for it … California also has some key species in place … like Mountain Lions.

What could ticks have to do with Mountain Lions? To understand this chain of causality, we have to start with deer. Little critters that inhabit the coats of deer are a favorite “all-you-can-eat buffet” for Black Legged Deer Ticks. And while the feast goes on and on, the deer does not get infected, it supplies food for an ever-increasing tick population and physically moves the ticks to new locales thereby providing fresh individuals to infect. Enter the Mountain Lion! Mountain Lions eat about one deer a week. They do not have Mountain Lions in the east, but we do. As a result, the deer population has exploded in the Northeast, but California populations are kept in check by our thoughtful Mountain Lions. Do we know all the answers? Not yet and maybe never, but remember it’s complicated!

Is our Western Fence Lizard a Super Hero? Maybe or maybe not. But it sure is an interesting little animal!

We are indebted to Gary Nafis (www.californiaherps.com) for all the wonderful

lizard photos in this Treasure Hunt.

In the beginning there were reeds and sedges

In the beginning there were reeds and sedges Bottom Line

Bottom Line

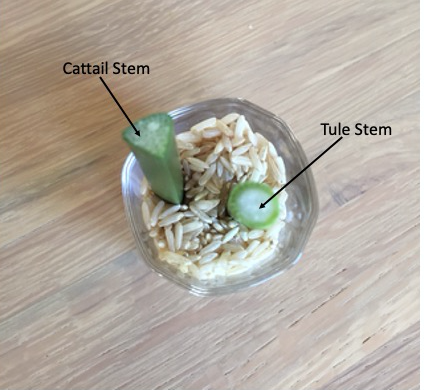

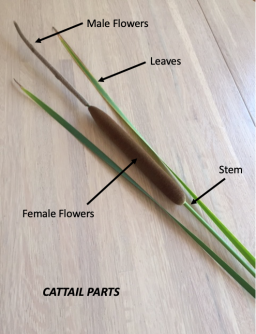

large diameter, brown, cylindrical female flower with a “fuzzy” appearance. This feature is responsible for the plant’s name and makes it easily identifiable as a “Cattail” … although it really looks more like a “corn dog!”

large diameter, brown, cylindrical female flower with a “fuzzy” appearance. This feature is responsible for the plant’s name and makes it easily identifiable as a “Cattail” … although it really looks more like a “corn dog!” Cattails are important to tiny fish, waterfowl and animals alike. Birds make use of these marshy plants for food and shelter, as well as a source for nesting material. During nesting season, one of my favorite birds, the Redwing Blackbird often makes its home in thick Cattail patches.

Cattails are important to tiny fish, waterfowl and animals alike. Birds make use of these marshy plants for food and shelter, as well as a source for nesting material. During nesting season, one of my favorite birds, the Redwing Blackbird often makes its home in thick Cattail patches.

Tules: I’m guessing the whole “Bulrush” thing started with the story of “Moses in the Bulrushes”. However, this “baby in the river” tale is not unique to Moses. It may have originated in the legend of Romulus and Remus who were left in the Tiber, or that of Sumerian King Sargon I, who was abandoned in a caulked basket in the Euphrates.

Tules: I’m guessing the whole “Bulrush” thing started with the story of “Moses in the Bulrushes”. However, this “baby in the river” tale is not unique to Moses. It may have originated in the legend of Romulus and Remus who were left in the Tiber, or that of Sumerian King Sargon I, who was abandoned in a caulked basket in the Euphrates.