The Most Wonderful Treasure….

As the end of the Lockdown approaches, I have been musing about how to “wrap up” our Treasure Hunts. How does one describe the entirety of the treasures of More Mesa … those few that I wrote about, and the hundreds of others that exist in this magical and remarkable place. Indeed, the most wonderful treasure on the whole South Coast is More Mesa itself!

What were our Treasure Hunts about? Over the past months, we discovered many of the individual treasures of More Mesa. We did this in fun looks at its trees, plants, birds, Insects, arachnids, reptiles, animals and even some man-made stuff. We reported on treasures that are native to our area, and even some that were imported here for various reasons and have since become difficult-to-control nightmares.

All of these treasures make their homes in one or more of the habitats of More Mesa. So … what’s the big deal? The big deal is that 80% of More Mesa has been identified as Environmentally Sensitive Habitat or ESH. ESH is the designation for a special place where plant and animal life, or their habitats, are rare or extremely valuable because of their special role in an ecosystem; one which could be easily disturbed or degraded … by us!

All of these treasures make their homes in one or more of the habitats of More Mesa. So … what’s the big deal? The big deal is that 80% of More Mesa has been identified as Environmentally Sensitive Habitat or ESH. ESH is the designation for a special place where plant and animal life, or their habitats, are rare or extremely valuable because of their special role in an ecosystem; one which could be easily disturbed or degraded … by us!

Now comes a really big AHA … More Mesa is extraordinary in that it contains five different, distinct and unique habitat types … more than any other open space on the South Coast! It begins with a distinct vegetation community created by differences in topography, soil types, sun exposure and moisture. Then each plant community, in its turn, determines the types of wildlife that will be present. Thus, three important factors, physical features, vegetation and wildlife, create a unique habitat. With that background in mind, we can explore where all the treasures we talked about for the past 15 months make their homes within their special habitats.

Trees Crave Lots of Water: We talked about four species of trees; Willows, Cottonwoods, Sycamores and Oaks. All these trees need water, and we typically find the first three somewhere very near water. Their habitat, Riparian Woodlands can be found on More Mesa near Atascadero Creek and its adjacent flood plains as well as canyons and ravines.

Oaks need water as well, but are well adapted by having an extremely long tap root that eventually finds water … somewhere. Oaks have their own special habitat which is called, appropriately enough, Oak Woodland. For me, having been a climber in my youth, this beautiful habitat is hauntingly reminiscent of the forests in the foothills of the Sierras.

Oaks need water as well, but are well adapted by having an extremely long tap root that eventually finds water … somewhere. Oaks have their own special habitat which is called, appropriately enough, Oak Woodland. For me, having been a climber in my youth, this beautiful habitat is hauntingly reminiscent of the forests in the foothills of the Sierras.

More Mesa’s Plants Live in all Habitats: Our plant Treasure Hunts had us looking for plants that live in soil, wet soil and water as well. We searched for Miner’s Lettuce, Elderberries, Datura and various water plants. We even devoted a whole issue to dreaded invasive plants; species brought to the Goleta Valley as cash crops, good feed for cattle or just by accident!

The Miner’s Lettuce we looked at in Spring likes the shade of an Oak Woodland, while Elderberry prefers a little water in its life and does well in Riparian Woodlands. Datura seemed to thrive in almost all habitats.

Vernal Pool 2002

Our issue on water plants looked at plants that populate Wetlands … like Atascadero Creek and its adjacent marshes, canyon and ravine bottoms, meadows and open water pools.

Our issue on water plants looked at plants that populate Wetlands … like Atascadero Creek and its adjacent marshes, canyon and ravine bottoms, meadows and open water pools.

However, the most remarkable Wetland we have on More Mesa is a Vernal Pool on the southeast corner. These very special and fast disappearing wetlands, are seasonal pools that fill with winter rainwater, and then dry out gradually thru the Spring and early Summer. Vernal Pools support a variety of rare water plants. Our own Vernal Pool was studied extensively the last time it filled, in Spring of 2019, and was subsequently identified as the most prolific Vernal Pool in all of the Goleta Valley. To learn more about Vernal Pools, and why the ones that remain are so very important, read about these unusual wetlands on our website.

The Coast Has a Special Habitat All its Own: As one strolls along the coast at the southern edge of More Mesa, you are likely to discover Deerweed, an extremely interesting plant we talked about when we wrote about bees. Remember how bees can see in the ultraviolet? This coastal path is also likely to give the visitor a good look at a Western Fence Lizard and perhaps a lone, impressive, and completely harmless, large Gopher Snake. A look skyward over the ocean might also include a Western Gull hunting for a sea food dinner.

The Coast Has a Special Habitat All its Own: As one strolls along the coast at the southern edge of More Mesa, you are likely to discover Deerweed, an extremely interesting plant we talked about when we wrote about bees. Remember how bees can see in the ultraviolet? This coastal path is also likely to give the visitor a good look at a Western Fence Lizard and perhaps a lone, impressive, and completely harmless, large Gopher Snake. A look skyward over the ocean might also include a Western Gull hunting for a sea food dinner.

The coastal walk, includes all of the fourth habitat on More Mesa, Coastal Bluff Scrub, a habitat that, when we are fortunate enough to get enough rain, offers us a spectacular late winter show. The star of this show is the California Brittle Bush, with its cast of hundreds of thousands of yellow blossoms decorating the top of the cliff and many feet below as well.

Mostly It’s Grass: The last habitat on More Mesa is also the largest … Grasslands … a habitat that can be found throughout level mesa areas and on some canyon slopes.

In the mid 1800s, when More Mesa was occupied by grazing cattle, grass was really important. And while More Mesa is no longer home to even a single cow, grasslands continue to play a critical ecosystem role. First, Grasslands are home to myriad species of small birds who eat seeds. And of vital importance, seeds and grasses provide food for small mammal populations … think Voles, Mice, Gophers, Rabbits and Squirrels. And you might remember the progression we talked about in earlier issues, wherein grass seeds provide food for small mammals and then small mammals serve as food for sensitive raptors as well as larger mammals. In other words, Grasslands are the cafeteria for almost all birds and many mammals.However, while small birds also make their homes in the Grasslands, raptors only use it as a cafeteria and generally live in other habitats … habitats with trees.

For example, and of major importance, in seasons with adequate rainfall, More Mesa can become home for up to 4 nesting pairs of our famous signature bird, the White-tailed Kite. Remarkably, in this year of extremely low rainfall, we have two adult pairs that are, even as I write this, feeding 6 hungry offspring!

We also looked at other birds in our Treasure Hunts, among them Great Blue Herons, Owls and Roadrunners. All of these, as well as the Kites, find food in the Grasslands of More Mesa, with the Roadrunner living there as well. Even the Peregrine Falcon, preferring birds for breakfast and dinner finds sustenance from the smaller birds that make their homes in the grasslands of More Mesa.

What about those larger mammals? We often have sightings of Bobcats, medium sized cats that feed on smaller mammals found on More Mesa. And, on another remarkable front, two Mountain Lions were spotted on the northwest part of More Mesa this year!

Big and tiny … our Treasure Hunts also looked at the Butterflies and Spiders found all over More Mesa’s Grasslands. And finally, the “man made stuff”, was a look at an important chapter in our country’s history and a fun departure from our usual hunts.

More Mesa is Part of a Bigger Picture: Habitats aside, it is important to remember that the canyons and ravines of More Mesa are linked to Atascadero Creek and larger regional ecosystems; systems providing wildlife migration corridors that reach all the way from the foothills to the shore.

Walking on More Mesa is a voyage back more than two centuries. Saving it preserves an important look at what was, all that we have lost and what we still can save. It is the last great place in Santa Barbara.

It has been an honor and a privilege to explore the treasures of More Mesa with you during this difficult and tumultuous time. Thank you for letting me come into your homes to share the wonder of this beautiful, magical piece of our history.

Look for more traditional news updates about More Mesa in the upcoming months and, most of all, thank you for reading the Treasure Hunts and thank you for caring about More Mesa … Valerie

Body Designed for Hunting: Though no bigger than a crow, and weighing about 1½ lbs., a Peregrine (sometimes called a “Duck Hawk”) is the largest and most powerful species in the falcon family. It sports a blue-grey back, barred white underparts, a black head and a distinctive yellow circle around the eyes. Its pointed wings can span almost 4 feet and

Body Designed for Hunting: Though no bigger than a crow, and weighing about 1½ lbs., a Peregrine (sometimes called a “Duck Hawk”) is the largest and most powerful species in the falcon family. It sports a blue-grey back, barred white underparts, a black head and a distinctive yellow circle around the eyes. Its pointed wings can span almost 4 feet and The bodies of Peregrine Falcons have many adaptations for hunting at high speeds. For starters, the shape of the Peregrine in a stoop has been compared by many to the shape of the B2 bomber. In addition, their nostrils guide shock waves of air to prevent the high pressure from damaging their lungs while they dive. This natural design actually influenced the design of the first jet engines!

The bodies of Peregrine Falcons have many adaptations for hunting at high speeds. For starters, the shape of the Peregrine in a stoop has been compared by many to the shape of the B2 bomber. In addition, their nostrils guide shock waves of air to prevent the high pressure from damaging their lungs while they dive. This natural design actually influenced the design of the first jet engines! Family Life: Mated for life, Peregrines return to their nest in February, to perform incredible courtship displays during which the male executes acrobatic aerial feats designed to woo his mate. He starts by suppling the female with food, often dropping it for her to catch mid-flight …. sometimes while she is flying upside down! She needs more food than he does, as is the case with many birds. This is because the female has greater body mass than the male. Some theories speculate that this dimorphism occurs so that she can produce larger eggs and easily incubate them.

Family Life: Mated for life, Peregrines return to their nest in February, to perform incredible courtship displays during which the male executes acrobatic aerial feats designed to woo his mate. He starts by suppling the female with food, often dropping it for her to catch mid-flight …. sometimes while she is flying upside down! She needs more food than he does, as is the case with many birds. This is because the female has greater body mass than the male. Some theories speculate that this dimorphism occurs so that she can produce larger eggs and easily incubate them.

You Find Them Where? Remember the two things that Peregrines need, “food and a high place to live”? As it turns out this requirement can be met in some very unlikely settings. While cities are generally thought to be the complete antithesis of wildlife habitat, some species actually thrive in concrete jungles … and the Peregrine Falcon is one of them. They nest on window ledges of skyscrapers and feed on introduced species such as doves, pigeons, and ducks. Urban living thus meets the same needs as would the more natural setting of an ocean sea cliff!

You Find Them Where? Remember the two things that Peregrines need, “food and a high place to live”? As it turns out this requirement can be met in some very unlikely settings. While cities are generally thought to be the complete antithesis of wildlife habitat, some species actually thrive in concrete jungles … and the Peregrine Falcon is one of them. They nest on window ledges of skyscrapers and feed on introduced species such as doves, pigeons, and ducks. Urban living thus meets the same needs as would the more natural setting of an ocean sea cliff! We Almost Lost Them Forever: Since the first half of the twentieth century, Peregrine Falcons have been exposed to dangerous threats that almost annihilated them. At first, they were heavily persecuted by gamekeepers and landowners, who were concerned about their stocks of game-birds. Then, during WW II, in a time before our digital world was even imagined, primitive methods of delivering messages were used. Specifically, thousands of Peregrines were also killed to protect the carrier pigeons carrying “important” military messages. After the war Peregrine numbers began to recover, and a full 10 years later, legislation finally outlawed their killing.

We Almost Lost Them Forever: Since the first half of the twentieth century, Peregrine Falcons have been exposed to dangerous threats that almost annihilated them. At first, they were heavily persecuted by gamekeepers and landowners, who were concerned about their stocks of game-birds. Then, during WW II, in a time before our digital world was even imagined, primitive methods of delivering messages were used. Specifically, thousands of Peregrines were also killed to protect the carrier pigeons carrying “important” military messages. After the war Peregrine numbers began to recover, and a full 10 years later, legislation finally outlawed their killing. Falconry has Been Around a Long Time: The recovery of North American Peregrines was greatly aided by the activities of falconers dedicated to raptor conservation. With the sport originating somewhere between the Near and Middle East, there is ample evidence that falconry has been practiced for at least 3,500 years, (While various groups through the ages have used raptors to catch birds, falconers use only falcons for this purpose.) Falconry also became especially popular with European nobility during the Middle Ages. Little has changed fundamentally in the sport — or, as some would argue — the art of falconry since the practice first began. Today, falconry continues in the same fashion as it began thousands of years ago. (You might even remember the use of falcons in an effort to discourage Western Gulls from invading the Oakland Baseball Stadium.) Finally, although subjected to shifting popularity and restrictions, interest in falconry continues, and the intense relationship between falconers and their birds remains extremely and mysteriously strong.

Falconry has Been Around a Long Time: The recovery of North American Peregrines was greatly aided by the activities of falconers dedicated to raptor conservation. With the sport originating somewhere between the Near and Middle East, there is ample evidence that falconry has been practiced for at least 3,500 years, (While various groups through the ages have used raptors to catch birds, falconers use only falcons for this purpose.) Falconry also became especially popular with European nobility during the Middle Ages. Little has changed fundamentally in the sport — or, as some would argue — the art of falconry since the practice first began. Today, falconry continues in the same fashion as it began thousands of years ago. (You might even remember the use of falcons in an effort to discourage Western Gulls from invading the Oakland Baseball Stadium.) Finally, although subjected to shifting popularity and restrictions, interest in falconry continues, and the intense relationship between falconers and their birds remains extremely and mysteriously strong.

A Grove of Cottonwood is a Sight to Behold: Today’s treasure is native to the Western States, a member of the Willow family and closely related to Poplars and Aspen. It’s the Black Cottonwood. Deriving its name from a rough and dark colored bark, Black Cottonwood is one of the fastest growing trees in North America. During spring and summer, it will increase its height by up to 6 feet, a yearly growth spurt which allows Cottonwoods to routinely reach a height of 100 feet. And there is a need to hurry … since they are not a long-lived species and may survive only 70-100 years in conditions that are less than ideal.

A Grove of Cottonwood is a Sight to Behold: Today’s treasure is native to the Western States, a member of the Willow family and closely related to Poplars and Aspen. It’s the Black Cottonwood. Deriving its name from a rough and dark colored bark, Black Cottonwood is one of the fastest growing trees in North America. During spring and summer, it will increase its height by up to 6 feet, a yearly growth spurt which allows Cottonwoods to routinely reach a height of 100 feet. And there is a need to hurry … since they are not a long-lived species and may survive only 70-100 years in conditions that are less than ideal. The lovely Cottonwood is tough and easy to grow as long as it is in sun, has good drainage and is near a water source. And while water is extremely important for young trees, larger trees are more drought resistant. Black Cottonwood leaves are 2-6 inches long, light green and oval to heart-shaped, with a point on the end. The leaf itself is attached to a long “stem-like” structure called a petiole, with the other end of the petiole being attached to a woody stem of the tree. Attachment of the petiole to the leaf is an important part of the story of Cottonwoods and Aspen.

The lovely Cottonwood is tough and easy to grow as long as it is in sun, has good drainage and is near a water source. And while water is extremely important for young trees, larger trees are more drought resistant. Black Cottonwood leaves are 2-6 inches long, light green and oval to heart-shaped, with a point on the end. The leaf itself is attached to a long “stem-like” structure called a petiole, with the other end of the petiole being attached to a woody stem of the tree. Attachment of the petiole to the leaf is an important part of the story of Cottonwoods and Aspen. It’s Spring Again … Procreation Time: Cottonwoods are dioecious, meaning that there are male trees and female trees. Early in spring, even before we see new leaves on the tree, both male and female trees flower, with inconspicuous catkins from 1 ½ to 3 inches long; males red and females green. Males catkins fall from the tree fairly quickly, releasing windborne pollen to find the catkins of a female tree. Pollenated female catkins become a series of buds, then flowers and finally thousands of seeds with their famous attached cottony parachutes. These windborne seeds create the famous Spring-early Summer “snow storms” that give Cottonwoods their name and reputation. Alas, male trees do not provide any snowstorms.

It’s Spring Again … Procreation Time: Cottonwoods are dioecious, meaning that there are male trees and female trees. Early in spring, even before we see new leaves on the tree, both male and female trees flower, with inconspicuous catkins from 1 ½ to 3 inches long; males red and females green. Males catkins fall from the tree fairly quickly, releasing windborne pollen to find the catkins of a female tree. Pollenated female catkins become a series of buds, then flowers and finally thousands of seeds with their famous attached cottony parachutes. These windborne seeds create the famous Spring-early Summer “snow storms” that give Cottonwoods their name and reputation. Alas, male trees do not provide any snowstorms.

Cottonwood -The love-Hate Relationship: While fast growth and wonderful shade are reasons enough to cherish Cottonwood, these trees possess many other fine qualities. In the wild, Cottonwood is one of the fastest trees to colonize unplanted areas, making it a solid choice for regions prone to flooding and soil erosion. It is used to stabilize streambanks, acts as a natural waterway filtration system to reduce sedimentation and creates groves that become natural windbreaks.

Cottonwood -The love-Hate Relationship: While fast growth and wonderful shade are reasons enough to cherish Cottonwood, these trees possess many other fine qualities. In the wild, Cottonwood is one of the fastest trees to colonize unplanted areas, making it a solid choice for regions prone to flooding and soil erosion. It is used to stabilize streambanks, acts as a natural waterway filtration system to reduce sedimentation and creates groves that become natural windbreaks. Wildlife Values Important: In spite of the fact that Cottonwoods are not worth much on the timber market, their cottony seeds cause problems in urban areas and they have several other annoying habits, they are one of the most widespread and important wildlife trees in the western United States and Canada. Their value lies not only in their beauty but the habitats they provide.

Wildlife Values Important: In spite of the fact that Cottonwoods are not worth much on the timber market, their cottony seeds cause problems in urban areas and they have several other annoying habits, they are one of the most widespread and important wildlife trees in the western United States and Canada. Their value lies not only in their beauty but the habitats they provide. Familiar Sounding Places: Cottonwoods are in the Poplar genus, and the Spanish name for Poplar is “álamo,” “Alamo” has lent itself to some famous places in America, such as the Alamo in San Antonio, site of a famous battle for Texan independence, as well as Los Alamos, New Mexico, site of American nuclear laboratories. However, the romantic sounding name of another New Mexican town, Alamogordo, actually means “the fat cottonwood tree.” (Not so glamorous.)

Familiar Sounding Places: Cottonwoods are in the Poplar genus, and the Spanish name for Poplar is “álamo,” “Alamo” has lent itself to some famous places in America, such as the Alamo in San Antonio, site of a famous battle for Texan independence, as well as Los Alamos, New Mexico, site of American nuclear laboratories. However, the romantic sounding name of another New Mexican town, Alamogordo, actually means “the fat cottonwood tree.” (Not so glamorous.)

Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count: Some of you may have seen a recent article in the Montecito Journal on the 121st Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count. This yearly winter event is North America’s longest-running citizen science bird project, with the data collected fueling Audubon’s work throughout the entire year. Data from the count is also shared with the scientific community, universities, wildlife groups, government agencies and the public. Although this year’s data are still being validated, you can get a sense of the size of this undertaking, by knowing that last year there were 62,000 Americans who participated in the count. These reporters submitted over 2000 observations.

Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count: Some of you may have seen a recent article in the Montecito Journal on the 121st Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count. This yearly winter event is North America’s longest-running citizen science bird project, with the data collected fueling Audubon’s work throughout the entire year. Data from the count is also shared with the scientific community, universities, wildlife groups, government agencies and the public. Although this year’s data are still being validated, you can get a sense of the size of this undertaking, by knowing that last year there were 62,000 Americans who participated in the count. These reporters submitted over 2000 observations.

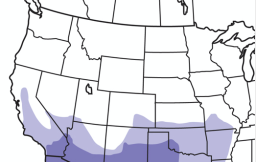

Rara Avis … a Rare Bird: This Treasure Hunt features a bird that has never been reported on More Mesa, until last Fall. It is the Greater Roadrunner; common in the Southwestern states of Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona, but seen much less often in California. Roadrunner’s favorite habitats include deserts, brush and grasslands. Although somewhat rare, the Roadrunner is a species that most of us over age 50 met when we were kids; in the famous Roadrunner cartoons. This “Classic” cartoon series, introduced in 1949*, was written by Michael Maltese and animated by Chuck Jones. It ended in 1963 when Warner Brothers closed its Animation Studio.

Rara Avis … a Rare Bird: This Treasure Hunt features a bird that has never been reported on More Mesa, until last Fall. It is the Greater Roadrunner; common in the Southwestern states of Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona, but seen much less often in California. Roadrunner’s favorite habitats include deserts, brush and grasslands. Although somewhat rare, the Roadrunner is a species that most of us over age 50 met when we were kids; in the famous Roadrunner cartoons. This “Classic” cartoon series, introduced in 1949*, was written by Michael Maltese and animated by Chuck Jones. It ended in 1963 when Warner Brothers closed its Animation Studio. Sound: Roadrunners do not go Beep-Beep or Meep-Meep; these sounds were created by the animator of the cartoon. However, the Plymouth Roadrunner automobile, manufactured between 1968 and 1980, was not only named after the cartoon, but Plymouth also bought the rights to the horn and its well-known Beep-Beep. Among several other sounds, including lots of bill clacking, the (non-gasoline powered) Roadrunner actually goes co-coo-coo-coo-coooooo in a series of 3–8 downward slurring notes. These vocalizations are typical of a bird in the Cuckoo family and … no surprise … the Roadrunner is identified as a fast-running ground Cuckoo.

Sound: Roadrunners do not go Beep-Beep or Meep-Meep; these sounds were created by the animator of the cartoon. However, the Plymouth Roadrunner automobile, manufactured between 1968 and 1980, was not only named after the cartoon, but Plymouth also bought the rights to the horn and its well-known Beep-Beep. Among several other sounds, including lots of bill clacking, the (non-gasoline powered) Roadrunner actually goes co-coo-coo-coo-coooooo in a series of 3–8 downward slurring notes. These vocalizations are typical of a bird in the Cuckoo family and … no surprise … the Roadrunner is identified as a fast-running ground Cuckoo. Population: Roadrunners were found in great numbers in Southwestern states like Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and California until the 1940s. At that time their population declined sharply, not because Coyotes were catching and eating them, but because they were shot and killed under an umbrella of federal and state bounties. Today however, loss of habitat is a much bigger threat. Massive development, especially in California, pushes Roadrunners out of their homes, fragments their territories, drives away prey and eliminates nesting sites. Maps of Roadrunner locations list populations in many parts of California as “uncommon”. And a 1994 scholarly paper on Roadrunners declared them extirpated; locally extinct in Santa Barbara. Guess what? They’re back!

Population: Roadrunners were found in great numbers in Southwestern states like Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and California until the 1940s. At that time their population declined sharply, not because Coyotes were catching and eating them, but because they were shot and killed under an umbrella of federal and state bounties. Today however, loss of habitat is a much bigger threat. Massive development, especially in California, pushes Roadrunners out of their homes, fragments their territories, drives away prey and eliminates nesting sites. Maps of Roadrunner locations list populations in many parts of California as “uncommon”. And a 1994 scholarly paper on Roadrunners declared them extirpated; locally extinct in Santa Barbara. Guess what? They’re back! Interesting and Different: Actual roadrunners are far more interesting than their cartoon counterparts. The Roadrunner, unlike most birds, runs rather than flies, and feeds on some of the most unappetizing animals imaginable. These include scorpions, black widows and even venomous rattlesnakes. In fact, as omnivores, they will eat anything that is alive, weighs less than a pound, is moving and is not poisonous! It is also curiously unafraid of humans. Typically, a Roadrunner will trot up close, cock its head and peer at us, raise and lower its mop of shaggy crest and flip its long tail expressively. (The long tail feathers provide balance not only when it is looking at you, but when it is running as well.) These unusual traits point to it being completely unafraid and undeniably zany! (After all, the cartoon was part of the “Looney Tunes”family.)

Interesting and Different: Actual roadrunners are far more interesting than their cartoon counterparts. The Roadrunner, unlike most birds, runs rather than flies, and feeds on some of the most unappetizing animals imaginable. These include scorpions, black widows and even venomous rattlesnakes. In fact, as omnivores, they will eat anything that is alive, weighs less than a pound, is moving and is not poisonous! It is also curiously unafraid of humans. Typically, a Roadrunner will trot up close, cock its head and peer at us, raise and lower its mop of shaggy crest and flip its long tail expressively. (The long tail feathers provide balance not only when it is looking at you, but when it is running as well.) These unusual traits point to it being completely unafraid and undeniably zany! (After all, the cartoon was part of the “Looney Tunes”family.) Not Much Reason to Fly: Because they can run fast and find almost all of their food on the ground, why bother to fly? Only if a Roadrunner has to escape a predator, reach a branch, or catch a flying insect, will it actually fly. The flight is then for very short distances, and only for a few seconds before it glides to a landing. This particular bird is simply not constructed for flying. The reason is that its skeleton cannot support a point of attachment for the large pectoral muscles required for prolonged and vigorous flight.

Not Much Reason to Fly: Because they can run fast and find almost all of their food on the ground, why bother to fly? Only if a Roadrunner has to escape a predator, reach a branch, or catch a flying insect, will it actually fly. The flight is then for very short distances, and only for a few seconds before it glides to a landing. This particular bird is simply not constructed for flying. The reason is that its skeleton cannot support a point of attachment for the large pectoral muscles required for prolonged and vigorous flight. Keeping Warm: On cool desert nights, Roadrunners enter a state of torpor by dropping their body temperatures; thereby conserving energy. To recover from their cold night of slumber, they spend the morning lying out in the sunlight, with their feathers raised to allow the sun to reach their black skin. If daytime temperatures drop in winter, they use the sun to warm up several times a day.

Keeping Warm: On cool desert nights, Roadrunners enter a state of torpor by dropping their body temperatures; thereby conserving energy. To recover from their cold night of slumber, they spend the morning lying out in the sunlight, with their feathers raised to allow the sun to reach their black skin. If daytime temperatures drop in winter, they use the sun to warm up several times a day. What About a Social Life? With all that chasing, “Roadrunner” did not have much chance for a social life. However, live Roadrunners are very serious about family matters. They defend their territory, have elaborate mating rituals, form life-long bonds and cooperatively work together in all aspects of reproduction. In order make the nest ready for eggs, each member of the pair has specific tasks. The male collects materials for the nest and the female builds it. She then lays 3-10 eggs. While both parents take turns incubating the eggs during the day, he gets all the night duty, because his body temperature does not drop after dark during nesting. Chicks hatch in 3 weeks and both parents will feed, protect and care for them for about a month. In favorable seasons (lots of food around) they can raise 3 broods of young in a single season.

What About a Social Life? With all that chasing, “Roadrunner” did not have much chance for a social life. However, live Roadrunners are very serious about family matters. They defend their territory, have elaborate mating rituals, form life-long bonds and cooperatively work together in all aspects of reproduction. In order make the nest ready for eggs, each member of the pair has specific tasks. The male collects materials for the nest and the female builds it. She then lays 3-10 eggs. While both parents take turns incubating the eggs during the day, he gets all the night duty, because his body temperature does not drop after dark during nesting. Chicks hatch in 3 weeks and both parents will feed, protect and care for them for about a month. In favorable seasons (lots of food around) they can raise 3 broods of young in a single season.

MMPC’s Signature Bird …

MMPC’s Signature Bird … White-tailed Kite: The beautiful White-tailed Kite is the signature bird of MMPC and has been associated with us since we began our work more than 20 years ago. Because Kites are so very special, they are one of only 12 fully protected birds in the state of California. Our state’s classification of “Fully Protected” was, and remains, a way to identify and provide additional protection to those animals that are rare or face possible extinction. Further, with regard to the Federal Government, even though the White-tailed Kite is not listed as under the Endangered Species Act, it receives protection under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Both of these are very serious protections!

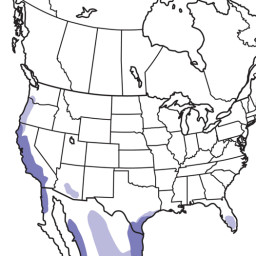

White-tailed Kite: The beautiful White-tailed Kite is the signature bird of MMPC and has been associated with us since we began our work more than 20 years ago. Because Kites are so very special, they are one of only 12 fully protected birds in the state of California. Our state’s classification of “Fully Protected” was, and remains, a way to identify and provide additional protection to those animals that are rare or face possible extinction. Further, with regard to the Federal Government, even though the White-tailed Kite is not listed as under the Endangered Species Act, it receives protection under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Both of these are very serious protections! Where Are They: White-tailed Kites can be found on the West and Gulf Coasts of the United States and into Central and South America. Locally, they can be observed year-round along the California Coast, in open grassland, marshes and agricultural areas. Closer to home, our own More Mesa has played a vital role in the recovery of the species, not only on the South Coast, but for the whole state. It has accomplished this because it offers the critical hunting and nesting habitat necessary to support high densities of Kites. Therefore, as agricultural land in the Goleta Valley continues to shrink rapidly, preservation of More Mesa becomes an increasingly crucial part of safeguarding this beautiful bird.

Where Are They: White-tailed Kites can be found on the West and Gulf Coasts of the United States and into Central and South America. Locally, they can be observed year-round along the California Coast, in open grassland, marshes and agricultural areas. Closer to home, our own More Mesa has played a vital role in the recovery of the species, not only on the South Coast, but for the whole state. It has accomplished this because it offers the critical hunting and nesting habitat necessary to support high densities of Kites. Therefore, as agricultural land in the Goleta Valley continues to shrink rapidly, preservation of More Mesa becomes an increasingly crucial part of safeguarding this beautiful bird. Beautiful and Easily Seen: The White-tailed Kite is a small hawk, easily identified by the all-white body and tail, and the black wing patches which are visible in flight or sitting. The open wings are sharply pointed with a three-foot span. Juveniles can be identified because their chest and head are lightly streaked with reddish/reddish orange color. And … all Kites have red eyes! But the dead-giveaway for a White-tailed Kite is their unusual hover flight when hunting. (More on this later.)

Beautiful and Easily Seen: The White-tailed Kite is a small hawk, easily identified by the all-white body and tail, and the black wing patches which are visible in flight or sitting. The open wings are sharply pointed with a three-foot span. Juveniles can be identified because their chest and head are lightly streaked with reddish/reddish orange color. And … all Kites have red eyes! But the dead-giveaway for a White-tailed Kite is their unusual hover flight when hunting. (More on this later.) Hunting Strategy: White-tailed Kites almost always hunt by hovering. (Watch this video to truly understand what is going on.) This distinctive hover behavior lasts up to a minute and ends with a successful prey strike only about 10% of the time.

Hunting Strategy: White-tailed Kites almost always hunt by hovering. (Watch this video to truly understand what is going on.) This distinctive hover behavior lasts up to a minute and ends with a successful prey strike only about 10% of the time. During “the hover”, the Kite is searching for prey, but in a very unusual fashion. As we have learned in past Treasure Hunts, avian vision is different for different species, and extremely well adapted in many remarkable and extraordinary ways. Their most incredible adaptation is their high resolution eyesight. However, the most unusual adaptation for avian vision, and raptors in particular, is the ability to see in the ultraviolet (UV). For those birds, who prey on rodents like voles and mice, this ability gives them a distinctive edge when hunting. This is because their prey, rodents, like many other species, use scent as a communication mechanism; marking territories, mating etc. Therefore, in these species, long scent trails become obvious markers of where the animal has been. An easier way to explain this is that rodents urinate by constantly “piddling”, leaving a trail behind them wherever they go. The usefulness of this habit to a hungry Kite takes a little explaining.

During “the hover”, the Kite is searching for prey, but in a very unusual fashion. As we have learned in past Treasure Hunts, avian vision is different for different species, and extremely well adapted in many remarkable and extraordinary ways. Their most incredible adaptation is their high resolution eyesight. However, the most unusual adaptation for avian vision, and raptors in particular, is the ability to see in the ultraviolet (UV). For those birds, who prey on rodents like voles and mice, this ability gives them a distinctive edge when hunting. This is because their prey, rodents, like many other species, use scent as a communication mechanism; marking territories, mating etc. Therefore, in these species, long scent trails become obvious markers of where the animal has been. An easier way to explain this is that rodents urinate by constantly “piddling”, leaving a trail behind them wherever they go. The usefulness of this habit to a hungry Kite takes a little explaining. Meeting Up: White-tailed Kites often have winter get-togethers in what is known as a communal roost. The “roost” is when a group of individuals, typically of the same species, congregate in an area based on some external signal. In the case of Kites, that signal is nightfall. Once the roost is established, the birds return to the same place every evening around dusk. The benefits of this gathering could include better hunting, warmth, protection from predators and just plain “getting together with the gang”. (I learned a new phrase for this benefit; “conspecific interactions”.) While watching Kites in a recent large roost (see photo by Barry Rowan), I was also told by a well-known and recognized local birder, that he thought the juveniles were especially focused on the roost so they could select the best partners for the spring nesting season. (Does this remind you of going to the dance at the gym to pick out the best guy or gal to be with?)

Meeting Up: White-tailed Kites often have winter get-togethers in what is known as a communal roost. The “roost” is when a group of individuals, typically of the same species, congregate in an area based on some external signal. In the case of Kites, that signal is nightfall. Once the roost is established, the birds return to the same place every evening around dusk. The benefits of this gathering could include better hunting, warmth, protection from predators and just plain “getting together with the gang”. (I learned a new phrase for this benefit; “conspecific interactions”.) While watching Kites in a recent large roost (see photo by Barry Rowan), I was also told by a well-known and recognized local birder, that he thought the juveniles were especially focused on the roost so they could select the best partners for the spring nesting season. (Does this remind you of going to the dance at the gym to pick out the best guy or gal to be with?) Keeping the Species From Disappearing … Chicks: More Mesa is considered the most important location for White-tailed Kite nesting on the South Coast. Because of the significance of this special bird, researchers have been studying and recording More Mesa’s Kites for nearly half a century. In pages 29-33 of our award winning More Mesa Handbook you can see that More Mesa consistently supports from one to three nesting sites with double-clutching (two families in one year) also observed in good rain years.

Keeping the Species From Disappearing … Chicks: More Mesa is considered the most important location for White-tailed Kite nesting on the South Coast. Because of the significance of this special bird, researchers have been studying and recording More Mesa’s Kites for nearly half a century. In pages 29-33 of our award winning More Mesa Handbook you can see that More Mesa consistently supports from one to three nesting sites with double-clutching (two families in one year) also observed in good rain years. December is courting season for White-tailed Kites. (Perhaps the males are seeking out that one female who caught their eye at the roost?) Courtship can often be in the form of ritualized displays. In one of these, a male offers prey to a female and then, in a spectacular aerial exchange, the female flies up to meet the male, turns upside-down, and grasps the prey. After they are both suitably impressed with one another, the two will form a monogamous pair in December, and stay together year-round. Nest building starts in January with White-tailed Kites typically choosing nurseries in the upper third of trees that may be 10–160 feet tall. The nest, which is made of twigs and lined with grass, weeds, or leaves can be built by the female or the pair. Its construction takes 1-4 weeks. When complete, the female usually lays 4 eggs and incubates them for about a month. During that time, the male brings food to the her and continues to do so until the eggs hatch. However, once the chicks have hatched, dad has to find food for both mom and the growing chicks! Mom is then responsible for transferring the food he delivers to the chicks in the nest. Even after the chicks have learned to fly, they are expecting free meals from dad. And, like most teenagers, they are pretty demanding! You can see that in the behavior in the photo below … where two chicks are competing over food that dad has procured. It is also evident in the header photo where the juveniles are chasing an adult with food. After those two-three exhausting months for mom and dad, the kids are on their own. It’s truly amazing that pairs still possess the energy to raise two broods in a season … even with plenty of food around!

December is courting season for White-tailed Kites. (Perhaps the males are seeking out that one female who caught their eye at the roost?) Courtship can often be in the form of ritualized displays. In one of these, a male offers prey to a female and then, in a spectacular aerial exchange, the female flies up to meet the male, turns upside-down, and grasps the prey. After they are both suitably impressed with one another, the two will form a monogamous pair in December, and stay together year-round. Nest building starts in January with White-tailed Kites typically choosing nurseries in the upper third of trees that may be 10–160 feet tall. The nest, which is made of twigs and lined with grass, weeds, or leaves can be built by the female or the pair. Its construction takes 1-4 weeks. When complete, the female usually lays 4 eggs and incubates them for about a month. During that time, the male brings food to the her and continues to do so until the eggs hatch. However, once the chicks have hatched, dad has to find food for both mom and the growing chicks! Mom is then responsible for transferring the food he delivers to the chicks in the nest. Even after the chicks have learned to fly, they are expecting free meals from dad. And, like most teenagers, they are pretty demanding! You can see that in the behavior in the photo below … where two chicks are competing over food that dad has procured. It is also evident in the header photo where the juveniles are chasing an adult with food. After those two-three exhausting months for mom and dad, the kids are on their own. It’s truly amazing that pairs still possess the energy to raise two broods in a season … even with plenty of food around!

Which Came First?: Ask any group of random folks what a kite is and they will say it’s the paper thing attached to a string that people fly on windy days in Mary Poppins. And it is. Ask the same group why our emblematic bird is called a Kite and they would probably say “because it looks like a “kite”. But it is believed that the bird actually came before the paper thing. Apparently, the word “kite” was derived from the Old English word “cyta” meaning to shoot up or go swiftly. Therefore, the word seemed like a good fit for a bird that could swoop on prey, hover in flight and soar. More than 20 Kite species are found all over the world so millions of people are able to marvel at their airborne ballets. As for the other “kite”, it is believed that the paper thing was originally constructed in China. Its form resembles the bird because the paper kite hovers nearly motionless in the air … similar to Kite behavior. However, it can never match the antics of a living Kite.

Which Came First?: Ask any group of random folks what a kite is and they will say it’s the paper thing attached to a string that people fly on windy days in Mary Poppins. And it is. Ask the same group why our emblematic bird is called a Kite and they would probably say “because it looks like a “kite”. But it is believed that the bird actually came before the paper thing. Apparently, the word “kite” was derived from the Old English word “cyta” meaning to shoot up or go swiftly. Therefore, the word seemed like a good fit for a bird that could swoop on prey, hover in flight and soar. More than 20 Kite species are found all over the world so millions of people are able to marvel at their airborne ballets. As for the other “kite”, it is believed that the paper thing was originally constructed in China. Its form resembles the bird because the paper kite hovers nearly motionless in the air … similar to Kite behavior. However, it can never match the antics of a living Kite.