WHAT HAPPENS WHEN HISTORY FALLS INTO THE SEA?

It All Starts with a Tiny Cactus

It All Starts with a Tiny Cactus

This Treasure Hunt is not about a gift from Mother Nature, but a story about a telephone line. It begins a hundred years ago with, surprisingly enough, a gift from Mother Nature, a tiny Prickly Pear Cactus. This little plant was on the property of the eldest child (Kate Bell) of one of our area’s most famous pioneers; Don Nicholas Den, owner of Rancho dos Pueblos. On Kate’s 76th

birthday, she had a giant celebration, convening the entire clan. And, as part of the celebration, she made a prophetic and wildly accurate prediction. She pointed to a struggling tiny cactus and offered that whomever sunk a well near that cactus would strike oil and become very rich.

As time went by, the tiny cactus prospered and became a large patch*. In 1927, the oily aroma in the area of the large patch launched the beginnings of oil exploration at Ellwood. But after more than a year of frustration, test wells continued to come up dry. However, in mid 1928 with one last gasp effort,  deeper and much closer to the cactus patch, they struck oil and struck it BIG! This one well alone yielded the richest oil yet found in California and ended up producing over a million barrels of high-quality crude. With two separate oil fields, one on land and one in the ocean, the coast at Ellwood quickly became a hot bed of oil activity; including extraction, refining, storage, and transportation. And because the area had so much going on, Kate Bell’s son-in-law feared that the revered cactus patch would be destroyed in the hustle and bustle of the oil field. So, he built an iron fence around the patch to protect it.

deeper and much closer to the cactus patch, they struck oil and struck it BIG! This one well alone yielded the richest oil yet found in California and ended up producing over a million barrels of high-quality crude. With two separate oil fields, one on land and one in the ocean, the coast at Ellwood quickly became a hot bed of oil activity; including extraction, refining, storage, and transportation. And because the area had so much going on, Kate Bell’s son-in-law feared that the revered cactus patch would be destroyed in the hustle and bustle of the oil field. So, he built an iron fence around the patch to protect it.

*The “patch” can still be seen today east of Haskell’s Beach … on a hillside below the Sandpiper Golf Course.

Enter A “Curious Someone” From Across the Sea

All during the 1930s, there was so much readily available product at Ellwood that tankers from nations all over the world came there to procure oil. The captain of one of these tankers was a highly esteemed Japanese Naval Officer named Kozo Nishino, one who had joined the submarine service in 1923 and captained several oil tankers during the 1930s. As a result of this experience he was very familiar with the Ellwood field and the surrounding coastline. It was on such a mission in the late 1930s, and while his tanker was being loaded, Commander Nishino decided to stroll along our lovely coast and happened upon Kate Bell’s cactus patch – now protected behind the iron fence. He decided that he would like a “cutting” of this strange plant for his garden back in Japan. Unfortunately, he fell into the patch and had to be pulled out by his crew. There were also other things that had to be pulled out … the cactus spines embedded in various parts of his body. While viewing the accident and recovery, American oil workers at the site offered only loud guffaws and embarrassing remarks. Commander Nishino was purported to have vowed revenge*.

*For the full story and wonderful photos of Kate Bell and her cactus see Goleta History.

In early 1941, with his career on a definite upward trajectory, Commander Nishino was awarded the newest, biggest “German-like” submarine: one that was the pride of the Japanese fleet. In fall of the year this sub played a part in the “run-up” to Pearl Harbor and was on patrol in the area on that fateful day. As soon as it was acknowledged that the attack was wildly successful, Captain Nishino was ordered to proceed to the west coast of the U.S. on a mission to attack America’s merchant ships.

Subs in Our Backyard

Early Japanese strategy was one of inflicting psychological, rather than physical, damage to the U.S. mainland. The campaign started a scant week after Pearl Harbor, when nine Japanese submarines were deployed to United States shores with orders to eliminate American supply ships and attack nine coastal cities and lighthouses up and down the Pacific coast. Almost all the targets were in California. This was a concerted effort to frighten the American public into thinking a large-scale attack on the mainland was coming next.

As a result, submarines were often spotted from shore in the Santa Barbara area and duly reported to Naval officers stationed here. These officers would then pass the information on to San Diego. On February 16,1942, an employee at the Ellwood oil field reported a sub to the Santa Barbara officer and it was immediately passed on. Three days later the same sub appeared, and the report was again made to the local naval officer who again passed it on to San Diego. This time the return message did not say “Thanks”. It said “Stop sending us these submarine sighting stories – the coast is full of California gray whales. That is what you are seeing, not subs.” The local officer groaned and reported back, “A whale is 20 feet long.* This submarine is 300 feet long.”

*Gray whales are actually more like 35-40 feet long, but they obviously did not have the same great whale books we have today.

Commander Nishino Returns to Ellwood

Captain Nishino, commander of one of the nine subs, was given three potential targets. When he checked them out, the first two were very heavily fortified and armed. Ellwood had not a single gun. So … four days after the “Those are whales, not subs report”, Captain Nishino returned, once again, to the scene of the Cactus Patch incident to lob 16-25, 5 ½ inch shells into the Ellwood coast. He timed the 20-minute shelling just as Americans were settling down around their radios to hear President Roosevelt’s fireside chat to the nation: a broadcast in honor of George Washington’s birthday. No one was killed or hurt during the attack and although the sub fired at a pair of oil storage tanks, they missed. Damage to the entire site was minimal perhaps $500 – $1000*.

Did Captain Nishino come back for revenge? Probably not. The captain was a career military officer, trained to follow orders and he most likely did just that. He did however, bend the truth more than a little bit when he radioed back to Japan saying he’d “left Santa Barbara in flames.”

The Ellwood shelling was a rousing success for Japan, because there were massive repercussions throughout America. Panic ensued on both coasts and especially in California. Most shameful was that the attack on Ellwood put an end to any shred of opposition to incarcerating Japanese Americans and ushered in a disgraceful period of illegal and unconstitutional internment. Those of Japanese descent were stripped of all their belongings, property etc. and 48 hours later shipped to camps around the country where they lived for more than 3 years. Of those 120,000 people, 70% were American citizens.

*To learn more about the Ellwood shelling, visit Goleta History.

So What Does This Have To Do With More Mesa?

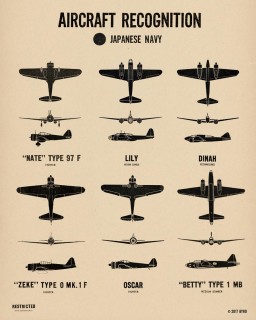

An America at war needed a way to decide if we were being attacked from the air. Because the west coast of the U. S. was viewed as very vulnerable, and as radar systems were in their infancy, aircraft-spotting stations in our area were  built very quickly after Pearl Harbor. Our “line” of spotting stations stretched from Tecolote Canyon to east of Hope Ranch. Stations were staffed by both men and women, all civilian volunteers; among them some of Santa Barbara’s most prominent citizens. These folks worked around the clock in two-hour shifts. Using binoculars and checking against charts of various Japanese planes, spotters reported to “filter” stations using a buried phone line. The filter stations would then forward authenticated reports to an Aircraft Warning Service.

built very quickly after Pearl Harbor. Our “line” of spotting stations stretched from Tecolote Canyon to east of Hope Ranch. Stations were staffed by both men and women, all civilian volunteers; among them some of Santa Barbara’s most prominent citizens. These folks worked around the clock in two-hour shifts. Using binoculars and checking against charts of various Japanese planes, spotters reported to “filter” stations using a buried phone line. The filter stations would then forward authenticated reports to an Aircraft Warning Service.

Our system was probably an early section of the Ground Observers Corps (GOC), a World War II Civil Defense program of the United States Army Air Forces to protect United States territory against air attack. By the beginning of November 1942, there were 1.5 million civilian observers in the GOC, who at 14,000 coastal observation posts performed naked eye and binocular searches to detect German or Japanese aircraft.

Our system was probably an early section of the Ground Observers Corps (GOC), a World War II Civil Defense program of the United States Army Air Forces to protect United States territory against air attack. By the beginning of November 1942, there were 1.5 million civilian observers in the GOC, who at 14,000 coastal observation posts performed naked eye and binocular searches to detect German or Japanese aircraft.

About the Telephone Line …

For those of you who read our periodic More Mesa updates, you are probably weary of our persistent nagging about the unstable nature of More Mesa’s cliffs. For those of you who never heard our warning message, here it is …

It is dangerous to go near the cliff edge at any time, and more importantly, never go near the edge after a rain.

What does this have to do with the telephone line? It’s all about “what went where” during WW II. During the Ground Observers Corps era, spotter shelters, built on concrete pads, were positioned relatively close to the edge of the cliff. Telephone lines to report sightings were buried much further back from the edge.

More Mesa’s extremely unstable shales erode, on average, about 10 inches a year. (Since I minored in math, I’ll do the numbers.) Ten inches a year since the beginning of WW II equates to the current cliff edge being roughly 65 feet further toward the mountains than it was at the beginning of WW II. The spotter shelters have long disappeared into the Pacific. And, almost all but a very few, and very tiny, sections of the phone lines are also gone. With luck, and extreme care, you might catch a glimpse of a small remnant of this important and bygone system at the cliff edge. In a few years these reminders too will vanish into the deep, marking the end of a tumultuous era that began almost a century ago.