Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count: Some of you may have seen a recent article in the Montecito Journal on the 121st Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count. This yearly winter event is North America’s longest-running citizen science bird project, with the data collected fueling Audubon’s work throughout the entire year. Data from the count is also shared with the scientific community, universities, wildlife groups, government agencies and the public. Although this year’s data are still being validated, you can get a sense of the size of this undertaking, by knowing that last year there were 62,000 Americans who participated in the count. These reporters submitted over 2000 observations.

Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count: Some of you may have seen a recent article in the Montecito Journal on the 121st Annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count. This yearly winter event is North America’s longest-running citizen science bird project, with the data collected fueling Audubon’s work throughout the entire year. Data from the count is also shared with the scientific community, universities, wildlife groups, government agencies and the public. Although this year’s data are still being validated, you can get a sense of the size of this undertaking, by knowing that last year there were 62,000 Americans who participated in the count. These reporters submitted over 2000 observations.

Santa Barbara has played a major role in this important piece of “Citizen Science” for many decades. An area 15 miles in diameter is selected for all participants, with our count centered at the intersection of Highway 154 and Foothill Road. Now for the “drum roll” … Santa Barbara recorded 206 separate species … the 5th highest number of species in the nation! This record is even more astounding when you consider that we are being compared with places that are under giant flyways of migrating species.

What has all of this to do with More Mesa? We are both proud and excited to report that, More Mesa alone, contributed 24% of the species reported in Santa Barbara’s impressive total. This is especially impactful when you consider that More Mesa represents only 0.02% of the land in the 15-mile diameter count area!

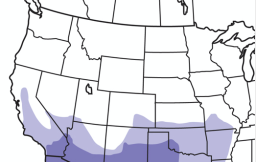

Rara Avis … a Rare Bird: This Treasure Hunt features a bird that has never been reported on More Mesa, until last Fall. It is the Greater Roadrunner; common in the Southwestern states of Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona, but seen much less often in California. Roadrunner’s favorite habitats include deserts, brush and grasslands. Although somewhat rare, the Roadrunner is a species that most of us over age 50 met when we were kids; in the famous Roadrunner cartoons. This “Classic” cartoon series, introduced in 1949*, was written by Michael Maltese and animated by Chuck Jones. It ended in 1963 when Warner Brothers closed its Animation Studio.

Rara Avis … a Rare Bird: This Treasure Hunt features a bird that has never been reported on More Mesa, until last Fall. It is the Greater Roadrunner; common in the Southwestern states of Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona, but seen much less often in California. Roadrunner’s favorite habitats include deserts, brush and grasslands. Although somewhat rare, the Roadrunner is a species that most of us over age 50 met when we were kids; in the famous Roadrunner cartoons. This “Classic” cartoon series, introduced in 1949*, was written by Michael Maltese and animated by Chuck Jones. It ended in 1963 when Warner Brothers closed its Animation Studio.

*In a strange coincidence, the Roadrunner became the state bird of New Mexico the same year as the Roadrunner Cartoon was introduced.

For those who remember that far back, the cartoons featured Wile E. Coyote and a slender blue and purple Roadrunner. It is reported that the animator was inspired to create these characters from Mark Twain’s book “Roughin It”, in which Twain postulated that hungry coyotes could hunt roadrunners. With a shift of “who chases who”, the animator remained adamant that the cartoons always adhered to a rule that the Roadrunner would humiliate, but never harm the hapless coyote. However, after watching many of these cartoons in preparation for this Treasure Hunt, I think that Wile was ALWAYS harmed; and most of the time he was barely recognizable in the final scene.

In each episode, the ever-hungry Coyote repeatedly attempts to somehow catch, and subsequently eat, the Road Runner. On occasion, Wile chases Roadrunner, but never, ever catches up to him. And instead of making use of his superb animal instincts, the Coyote employs absurdly complex contraptions (think Rube Goldberg) to try to capture his prey. These comically backfire, with the Coyote most often getting improbably injured in a slapstick calamity. Many of the items for the contrivances are mail ordered (pre-Amazon) from a variety of companies … all named Acme.

Reality: To ensure that your knowledge of Roadrunners has even a modicum of accuracy, I would like to point out some physical facts of life; for both Coyotes and Roadrunners. To start with, I think they have little contact with one another when they are not in a cartoon.

Size: Coyote and Roadrunner are often portrayed about the same size, or Coyote about 1/3 larger than Roadrunner. The Roadrunner is 22-24 inches from tail to beak and weighs somewhere between ½ and 1 pound. A coyote is much bigger and weighs more; as in 3 feet long and up to 43 pounds.

Speed: In all episodes but one, Coyote chases, but never catches the Roadrunner, despite the fact that a Roadrunner averages 15 mph (sometimes sprints as high as 20 mph) and a Coyote clocks in at 40 mph.

Age: While the classic cartoon Roadrunner and its spin-offs lasted a couple of decades, live Roadrunners have a life span of 7-8 years max.

Sound: Roadrunners do not go Beep-Beep or Meep-Meep; these sounds were created by the animator of the cartoon. However, the Plymouth Roadrunner automobile, manufactured between 1968 and 1980, was not only named after the cartoon, but Plymouth also bought the rights to the horn and its well-known Beep-Beep. Among several other sounds, including lots of bill clacking, the (non-gasoline powered) Roadrunner actually goes co-coo-coo-coo-coooooo in a series of 3–8 downward slurring notes. These vocalizations are typical of a bird in the Cuckoo family and … no surprise … the Roadrunner is identified as a fast-running ground Cuckoo.

Sound: Roadrunners do not go Beep-Beep or Meep-Meep; these sounds were created by the animator of the cartoon. However, the Plymouth Roadrunner automobile, manufactured between 1968 and 1980, was not only named after the cartoon, but Plymouth also bought the rights to the horn and its well-known Beep-Beep. Among several other sounds, including lots of bill clacking, the (non-gasoline powered) Roadrunner actually goes co-coo-coo-coo-coooooo in a series of 3–8 downward slurring notes. These vocalizations are typical of a bird in the Cuckoo family and … no surprise … the Roadrunner is identified as a fast-running ground Cuckoo.

Population: Roadrunners were found in great numbers in Southwestern states like Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and California until the 1940s. At that time their population declined sharply, not because Coyotes were catching and eating them, but because they were shot and killed under an umbrella of federal and state bounties. Today however, loss of habitat is a much bigger threat. Massive development, especially in California, pushes Roadrunners out of their homes, fragments their territories, drives away prey and eliminates nesting sites. Maps of Roadrunner locations list populations in many parts of California as “uncommon”. And a 1994 scholarly paper on Roadrunners declared them extirpated; locally extinct in Santa Barbara. Guess what? They’re back!

Population: Roadrunners were found in great numbers in Southwestern states like Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma and California until the 1940s. At that time their population declined sharply, not because Coyotes were catching and eating them, but because they were shot and killed under an umbrella of federal and state bounties. Today however, loss of habitat is a much bigger threat. Massive development, especially in California, pushes Roadrunners out of their homes, fragments their territories, drives away prey and eliminates nesting sites. Maps of Roadrunner locations list populations in many parts of California as “uncommon”. And a 1994 scholarly paper on Roadrunners declared them extirpated; locally extinct in Santa Barbara. Guess what? They’re back!

Interesting and Different: Actual roadrunners are far more interesting than their cartoon counterparts. The Roadrunner, unlike most birds, runs rather than flies, and feeds on some of the most unappetizing animals imaginable. These include scorpions, black widows and even venomous rattlesnakes. In fact, as omnivores, they will eat anything that is alive, weighs less than a pound, is moving and is not poisonous! It is also curiously unafraid of humans. Typically, a Roadrunner will trot up close, cock its head and peer at us, raise and lower its mop of shaggy crest and flip its long tail expressively. (The long tail feathers provide balance not only when it is looking at you, but when it is running as well.) These unusual traits point to it being completely unafraid and undeniably zany! (After all, the cartoon was part of the “Looney Tunes”family.)

Interesting and Different: Actual roadrunners are far more interesting than their cartoon counterparts. The Roadrunner, unlike most birds, runs rather than flies, and feeds on some of the most unappetizing animals imaginable. These include scorpions, black widows and even venomous rattlesnakes. In fact, as omnivores, they will eat anything that is alive, weighs less than a pound, is moving and is not poisonous! It is also curiously unafraid of humans. Typically, a Roadrunner will trot up close, cock its head and peer at us, raise and lower its mop of shaggy crest and flip its long tail expressively. (The long tail feathers provide balance not only when it is looking at you, but when it is running as well.) These unusual traits point to it being completely unafraid and undeniably zany! (After all, the cartoon was part of the “Looney Tunes”family.)

Not Much Reason to Fly: Because they can run fast and find almost all of their food on the ground, why bother to fly? Only if a Roadrunner has to escape a predator, reach a branch, or catch a flying insect, will it actually fly. The flight is then for very short distances, and only for a few seconds before it glides to a landing. This particular bird is simply not constructed for flying. The reason is that its skeleton cannot support a point of attachment for the large pectoral muscles required for prolonged and vigorous flight.

Not Much Reason to Fly: Because they can run fast and find almost all of their food on the ground, why bother to fly? Only if a Roadrunner has to escape a predator, reach a branch, or catch a flying insect, will it actually fly. The flight is then for very short distances, and only for a few seconds before it glides to a landing. This particular bird is simply not constructed for flying. The reason is that its skeleton cannot support a point of attachment for the large pectoral muscles required for prolonged and vigorous flight.

Keeping Warm: On cool desert nights, Roadrunners enter a state of torpor by dropping their body temperatures; thereby conserving energy. To recover from their cold night of slumber, they spend the morning lying out in the sunlight, with their feathers raised to allow the sun to reach their black skin. If daytime temperatures drop in winter, they use the sun to warm up several times a day.

Keeping Warm: On cool desert nights, Roadrunners enter a state of torpor by dropping their body temperatures; thereby conserving energy. To recover from their cold night of slumber, they spend the morning lying out in the sunlight, with their feathers raised to allow the sun to reach their black skin. If daytime temperatures drop in winter, they use the sun to warm up several times a day.

What About a Social Life? With all that chasing, “Roadrunner” did not have much chance for a social life. However, live Roadrunners are very serious about family matters. They defend their territory, have elaborate mating rituals, form life-long bonds and cooperatively work together in all aspects of reproduction. In order make the nest ready for eggs, each member of the pair has specific tasks. The male collects materials for the nest and the female builds it. She then lays 3-10 eggs. While both parents take turns incubating the eggs during the day, he gets all the night duty, because his body temperature does not drop after dark during nesting. Chicks hatch in 3 weeks and both parents will feed, protect and care for them for about a month. In favorable seasons (lots of food around) they can raise 3 broods of young in a single season.

What About a Social Life? With all that chasing, “Roadrunner” did not have much chance for a social life. However, live Roadrunners are very serious about family matters. They defend their territory, have elaborate mating rituals, form life-long bonds and cooperatively work together in all aspects of reproduction. In order make the nest ready for eggs, each member of the pair has specific tasks. The male collects materials for the nest and the female builds it. She then lays 3-10 eggs. While both parents take turns incubating the eggs during the day, he gets all the night duty, because his body temperature does not drop after dark during nesting. Chicks hatch in 3 weeks and both parents will feed, protect and care for them for about a month. In favorable seasons (lots of food around) they can raise 3 broods of young in a single season.

In the area of reproduction, Roadrunners are model parents and the absolute antihesis of their Cuckoo relatives. Many other Cuckoos NEVER build nests, but always lay their eggs in other bird’s nests and trust that the parents of the invaded nests will raise their young for them!

Where Are They in Winter? A puzzling question is why Roadrunners are observed much less frequently in winter months. Although there is no definitive answer as to where the Roadrunners are, there is some speculation about what may be going on. Migration is impossible because they can’t fly for more than a few seconds. Some observers have theorized that they hibernate, but thus far there is no evidence supporting that hypothesis. Others offer the possibility that they go into their “nighttime torpor state” for a long period. Unhappily, there is no evidence for that either. Maybe they have immigrated to More Mesa because of our great climate?

For a quick overview of this zany, unbirdlike bird take a look at this short video from the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

We are grateful and truly indebted to Doris Evans of Tucson Arizona for her wonderful and detailed photos of a pair of Roadrunner parents and how they raised and cared for their young. Many thanks Doris!

Stay safe … Valerie