There are Trees…and Then There are “Trees”

There are Trees…and Then There are “Trees”

If trees had personalities, I would have to characterize the Tamarisk, of our last Treasure Hunt, as the personification of evil, and today’s Treasure Hunt, as the personification of good. The California Sycamore is beautiful and interesting…in a different way…and during every season of the year. Moreover, it willingly offers sustenance, shelter, shade and safety to critters of all kinds…including us. After learning about our native Sycamore these past days, I can honestly say, I really love this tree!

California Sycamore

The California Sycamore, also known as the Western Sycamore, the California Plane and by several other names, can grow to 100 feet, with a trunk diameter as large as 3 feet. As a young tree, the Sycamore is pyramidal, but as it grows, the trunk generally divides into two or more large trunks which then split into many massive limbs and branches…giving the tree a wondrous rambling, often unsymmetrical, quality that just adds to its beauty.

The five-pointed green leaves of this lovely tree are extremely large, in fact the largest leaves of any native plant in North America. Moreover, when leaves first emerge, they are “fuzzy” on the top side and “very fuzzy” on the bottom side. But unlike many of our native trees, our Sycamore is deciduous, so that when the weather gets colder and the days shorter, these huge leaves put on a “fall show” by turning a striking golden and orangish color. And to provide a color show in winter, the tree boldly displays its bark, which is an attractive patchwork of white, tawny beige, pinkish gray, and pale brown. Indeed, some have described Sycamore bark as looking like a jig-saw puzzle. This colorful and interesting tree is native only to coastal California and the Baja, with its favorite habitats being canyons, floodplains and along streams. And like a few of the native trees of our area, it can live up to 250 years.

It’s Spring and Procreation is in the Air

The reproductive process for Sycamores starts in very early Spring. Both female and male reproductive organs can be found on the same tree. Male flowers form into small greenish spheres on “strings” that fall to the ground after the pollen of these flowers is released. The hope is that wind will carry

pollen from the male flowers to the dense reddish female flowers. These are larger spheres that look like fuzzy gum balls on a string, and are found on the same, or other, Sycamores. Once pollinated, the fruits of this tree are produced in the form of seed balls; golf-ball sized heads of tufted “fruits”, with each fruit containing a single seed. Three to seven of these balls hang on a stalk*, dry out, and then once again, call upon the wind to disperse the seeds for the new generation. To ensure seed dispersal, the individual carriers of the fruits have tufts of hair that act as parachutes…to catch the wind and travel long distances. This is especially helpful when there is a need to rapidly reestablish the species after a flood…smart Sycamore!

*Mature fruits can be seen in the photo at the top of this page.

The Sycamore is the Giving Tree

Sycamores give of themselves for critters all the way from small insects to large mammals like us. Starting with tiny animals, evidence of the use of Sycamore leaves for food may be found when you see holes its leaves. The holes tell you that the Sycamore Tussock Moth

caterpillar has been lunching. If you find a leaf with holes, you may also note that this caterpillar, and anything else that feeds on the leaves, does not particularly like the thick fuzzy coat on the leaves, or on new stems, so it pushes all that material to the side before dining. In some areas, the Western Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly also lays its eggs on Sycamore leaves…so its caterpillars may feast on them as well. Squirrels and other small rodents and birds, feed on the seeds of the Sycamore, while the bark is a dinner for beavers and fox squirrels. And at the top, these tall trees also provide safe nesting sites for many species of birds.

Sycamores have been giving to humans for a very long time. Native Americans used the inner bark for food and medicinal purposes, the leaves to wrap bread during baking, and branches in house construction. And after Europeans and “Yankees” arrived in California, our Sycamores were so prominent on the Central Coast that they were often used as landmarks. For example, newcomers to the Goleta Valley used sycamores as markers for property limits. Still living, and probably 250 years old, are two famous and gigantic Sycamores known as the Witness Tree and the Sister Witness Tree.

The Witness Tree still exists in the middle of the Butler Center on Hollister Avenue…surviving a recent fall of one large limb. Its relative, the Sister Witness Tree, just across the street, is credited with being the largest California Sycamore in the United States. These two trees are incredibly important as they were native before Europeans arrived on our coast and being genetically pure…they are extremely rare!

A little later, one tree, which stood on the south end of Milpas Street reportedly was used as a make-shift light house. Residents of Santa Barbara were purported to have hung lanterns in its upper branches to guide offshore sailing ships. However, this explanation for the lanterns probably does not tell the whole story.

The Whole Story

The Whole Story

During the period when California was part of the Spanish empire, “the Crown” insisted that all goods to California must come from Spanish merchants. To enforce this unenforceable edict, they levied onerous customs duties on all goods that came from “Yankee” ports…like Boston. Sometimes these duties were as high as 100% of the value of the goods. The law was unenforceable because, beside the fact that there were not enough Spanish ships or goods to meet the demand, there were not enough Spanish officials in the colonies to enforce the law. So…in the late 1790s and early 1800s smuggling became a way of life all up and down the California coast. Since it would be another 70+ years for Stearn’s Wharf to be built, goods destined for Santa Barbara were offloaded onto smaller boats or simply thrown overboard to be retrieved on shore. For smugglers, this clandestine activity went on during the night, when the Customs office was closed. It is therefore, most likely the light in the Sycamore was probably used to indicate to the smugglers where the goods should be put overboard. Yankee goods made life easier for early Californians, and once again, our lovely Sycamore was part of it!

The importance of caring for the tree that gives and gives may not be recognized by everyone. It is, however, recognized by the state of California! In 2006 the California Sycamore was added to the list of trees in our state that are “fully protected”.

Where Are They?

Once you can recognize Sycamores, you will see they can be found all

over Santa Barbara. they grow wild in creeks and canyons and have been

Sycamore on Atascadero Creek

planted in many beautiful and special places all around Santa Barbara…places like the Museum of Natural History, Oak Park and along the Atascadero Creek bike path.They have also been welcomed in private yards, as well as beautifying freeway entrances, exits and parkways. The Sycamore is a tree for all…and we should be very proud of this truly “giving” native being such a big part of our lovely and special little town.

We are indebted to Santa Barbara Beautiful, University of Redlands and Ken Knight for much valuable information on the California Sycamore.

Remember: Six Feet Apart and Stay Safe,

Valerie

Some invasive plants move from their home territories via stealth. They hitchhike on boots, backpacks, clothing, packaging containers and ship bottoms. But, by in large, most were purposely transported from their homeland by humans who thought they were treasures that would be valuable in other, far-away places.

Some invasive plants move from their home territories via stealth. They hitchhike on boots, backpacks, clothing, packaging containers and ship bottoms. But, by in large, most were purposely transported from their homeland by humans who thought they were treasures that would be valuable in other, far-away places.

This treasure, also known as salt cedar, is a shrub or small tree originally from Eurasia and Africa. It took root, literally and figuratively, about 200 years ago…and did so with the blessing of the federal government. After importation, it was sometimes used as an ornamental or as a windbreak.

This treasure, also known as salt cedar, is a shrub or small tree originally from Eurasia and Africa. It took root, literally and figuratively, about 200 years ago…and did so with the blessing of the federal government. After importation, it was sometimes used as an ornamental or as a windbreak.

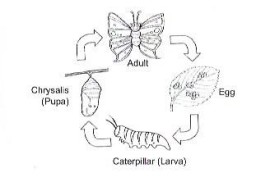

First the Birds, then the Bees and now … the Butterflies

First the Birds, then the Bees and now … the Butterflies

Eggs begin a new cycle and are laid on plants that the caterpillar likes to eat … and the caterpillar is usually a very picky eater!

Eggs begin a new cycle and are laid on plants that the caterpillar likes to eat … and the caterpillar is usually a very picky eater!