WHAT HAPPENS WHEN HISTORY FALLS INTO THE SEA?

It All Starts with a Tiny Cactus

It All Starts with a Tiny Cactus

This Treasure Hunt is not about a gift from Mother Nature, but a story about a telephone line. It begins a hundred years ago with, surprisingly enough, a gift from Mother Nature, a tiny Prickly Pear Cactus. This little plant was on the property of the eldest child (Kate Bell) of one of our area’s most famous pioneers; Don Nicholas Den, owner of Rancho dos Pueblos. On Kate’s 76th

birthday, she had a giant celebration, convening the entire clan. And, as part of the celebration, she made a prophetic and wildly accurate prediction. She pointed to a struggling tiny cactus and offered that whomever sunk a well near that cactus would strike oil and become very rich.

As time went by, the tiny cactus prospered and became a large patch*. In 1927, the oily aroma in the area of the large patch launched the beginnings of oil exploration at Ellwood. But after more than a year of frustration, test wells continued to come up dry. However, in mid 1928 with one last gasp effort,  deeper and much closer to the cactus patch, they struck oil and struck it BIG! This one well alone yielded the richest oil yet found in California and ended up producing over a million barrels of high-quality crude. With two separate oil fields, one on land and one in the ocean, the coast at Ellwood quickly became a hot bed of oil activity; including extraction, refining, storage, and transportation. And because the area had so much going on, Kate Bell’s son-in-law feared that the revered cactus patch would be destroyed in the hustle and bustle of the oil field. So, he built an iron fence around the patch to protect it.

deeper and much closer to the cactus patch, they struck oil and struck it BIG! This one well alone yielded the richest oil yet found in California and ended up producing over a million barrels of high-quality crude. With two separate oil fields, one on land and one in the ocean, the coast at Ellwood quickly became a hot bed of oil activity; including extraction, refining, storage, and transportation. And because the area had so much going on, Kate Bell’s son-in-law feared that the revered cactus patch would be destroyed in the hustle and bustle of the oil field. So, he built an iron fence around the patch to protect it.

*The “patch” can still be seen today east of Haskell’s Beach … on a hillside below the Sandpiper Golf Course.

Enter A “Curious Someone” From Across the Sea

All during the 1930s, there was so much readily available product at Ellwood that tankers from nations all over the world came there to procure oil. The captain of one of these tankers was a highly esteemed Japanese Naval Officer named Kozo Nishino, one who had joined the submarine service in 1923 and captained several oil tankers during the 1930s. As a result of this experience he was very familiar with the Ellwood field and the surrounding coastline. It was on such a mission in the late 1930s, and while his tanker was being loaded, Commander Nishino decided to stroll along our lovely coast and happened upon Kate Bell’s cactus patch – now protected behind the iron fence. He decided that he would like a “cutting” of this strange plant for his garden back in Japan. Unfortunately, he fell into the patch and had to be pulled out by his crew. There were also other things that had to be pulled out … the cactus spines embedded in various parts of his body. While viewing the accident and recovery, American oil workers at the site offered only loud guffaws and embarrassing remarks. Commander Nishino was purported to have vowed revenge*.

*For the full story and wonderful photos of Kate Bell and her cactus see Goleta History.

In early 1941, with his career on a definite upward trajectory, Commander Nishino was awarded the newest, biggest “German-like” submarine: one that was the pride of the Japanese fleet. In fall of the year this sub played a part in the “run-up” to Pearl Harbor and was on patrol in the area on that fateful day. As soon as it was acknowledged that the attack was wildly successful, Captain Nishino was ordered to proceed to the west coast of the U.S. on a mission to attack America’s merchant ships.

Subs in Our Backyard

Early Japanese strategy was one of inflicting psychological, rather than physical, damage to the U.S. mainland. The campaign started a scant week after Pearl Harbor, when nine Japanese submarines were deployed to United States shores with orders to eliminate American supply ships and attack nine coastal cities and lighthouses up and down the Pacific coast. Almost all the targets were in California. This was a concerted effort to frighten the American public into thinking a large-scale attack on the mainland was coming next.

As a result, submarines were often spotted from shore in the Santa Barbara area and duly reported to Naval officers stationed here. These officers would then pass the information on to San Diego. On February 16,1942, an employee at the Ellwood oil field reported a sub to the Santa Barbara officer and it was immediately passed on. Three days later the same sub appeared, and the report was again made to the local naval officer who again passed it on to San Diego. This time the return message did not say “Thanks”. It said “Stop sending us these submarine sighting stories – the coast is full of California gray whales. That is what you are seeing, not subs.” The local officer groaned and reported back, “A whale is 20 feet long.* This submarine is 300 feet long.”

*Gray whales are actually more like 35-40 feet long, but they obviously did not have the same great whale books we have today.

Commander Nishino Returns to Ellwood

Captain Nishino, commander of one of the nine subs, was given three potential targets. When he checked them out, the first two were very heavily fortified and armed. Ellwood had not a single gun. So … four days after the “Those are whales, not subs report”, Captain Nishino returned, once again, to the scene of the Cactus Patch incident to lob 16-25, 5 ½ inch shells into the Ellwood coast. He timed the 20-minute shelling just as Americans were settling down around their radios to hear President Roosevelt’s fireside chat to the nation: a broadcast in honor of George Washington’s birthday. No one was killed or hurt during the attack and although the sub fired at a pair of oil storage tanks, they missed. Damage to the entire site was minimal perhaps $500 – $1000*.

Did Captain Nishino come back for revenge? Probably not. The captain was a career military officer, trained to follow orders and he most likely did just that. He did however, bend the truth more than a little bit when he radioed back to Japan saying he’d “left Santa Barbara in flames.”

The Ellwood shelling was a rousing success for Japan, because there were massive repercussions throughout America. Panic ensued on both coasts and especially in California. Most shameful was that the attack on Ellwood put an end to any shred of opposition to incarcerating Japanese Americans and ushered in a disgraceful period of illegal and unconstitutional internment. Those of Japanese descent were stripped of all their belongings, property etc. and 48 hours later shipped to camps around the country where they lived for more than 3 years. Of those 120,000 people, 70% were American citizens.

*To learn more about the Ellwood shelling, visit Goleta History.

So What Does This Have To Do With More Mesa?

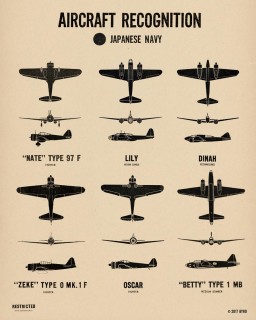

An America at war needed a way to decide if we were being attacked from the air. Because the west coast of the U. S. was viewed as very vulnerable, and as radar systems were in their infancy, aircraft-spotting stations in our area were  built very quickly after Pearl Harbor. Our “line” of spotting stations stretched from Tecolote Canyon to east of Hope Ranch. Stations were staffed by both men and women, all civilian volunteers; among them some of Santa Barbara’s most prominent citizens. These folks worked around the clock in two-hour shifts. Using binoculars and checking against charts of various Japanese planes, spotters reported to “filter” stations using a buried phone line. The filter stations would then forward authenticated reports to an Aircraft Warning Service.

built very quickly after Pearl Harbor. Our “line” of spotting stations stretched from Tecolote Canyon to east of Hope Ranch. Stations were staffed by both men and women, all civilian volunteers; among them some of Santa Barbara’s most prominent citizens. These folks worked around the clock in two-hour shifts. Using binoculars and checking against charts of various Japanese planes, spotters reported to “filter” stations using a buried phone line. The filter stations would then forward authenticated reports to an Aircraft Warning Service.

Our system was probably an early section of the Ground Observers Corps (GOC), a World War II Civil Defense program of the United States Army Air Forces to protect United States territory against air attack. By the beginning of November 1942, there were 1.5 million civilian observers in the GOC, who at 14,000 coastal observation posts performed naked eye and binocular searches to detect German or Japanese aircraft.

Our system was probably an early section of the Ground Observers Corps (GOC), a World War II Civil Defense program of the United States Army Air Forces to protect United States territory against air attack. By the beginning of November 1942, there were 1.5 million civilian observers in the GOC, who at 14,000 coastal observation posts performed naked eye and binocular searches to detect German or Japanese aircraft.

About the Telephone Line …

For those of you who read our periodic More Mesa updates, you are probably weary of our persistent nagging about the unstable nature of More Mesa’s cliffs. For those of you who never heard our warning message, here it is …

It is dangerous to go near the cliff edge at any time, and more importantly, never go near the edge after a rain.

What does this have to do with the telephone line? It’s all about “what went where” during WW II. During the Ground Observers Corps era, spotter shelters, built on concrete pads, were positioned relatively close to the edge of the cliff. Telephone lines to report sightings were buried much further back from the edge.

More Mesa’s extremely unstable shales erode, on average, about 10 inches a year. (Since I minored in math, I’ll do the numbers.) Ten inches a year since the beginning of WW II equates to the current cliff edge being roughly 65 feet further toward the mountains than it was at the beginning of WW II. The spotter shelters have long disappeared into the Pacific. And, almost all but a very few, and very tiny, sections of the phone lines are also gone. With luck, and extreme care, you might catch a glimpse of a small remnant of this important and bygone system at the cliff edge. In a few years these reminders too will vanish into the deep, marking the end of a tumultuous era that began almost a century ago.

Lizard … Bad Guy or Superhero?

Lizard … Bad Guy or Superhero? decided that the only reason I even thought about this issue was the expression “Lounge Lizard”; originally coined by the Flappers of the 1920s and used to describe men who hung around bars trying to pick up women … preferably rich ones. Apparently, the term has resurfaced every decade during the past 100 years and is still in use. With this flimsy negative evidence, and what follows, you decide whether the Western Fence Lizard may qualify as a Superhero.

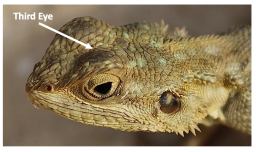

decided that the only reason I even thought about this issue was the expression “Lounge Lizard”; originally coined by the Flappers of the 1920s and used to describe men who hung around bars trying to pick up women … preferably rich ones. Apparently, the term has resurfaced every decade during the past 100 years and is still in use. With this flimsy negative evidence, and what follows, you decide whether the Western Fence Lizard may qualify as a Superhero. Of the three common lizards found on More Mesa, the Western Fence Lizard, also called Bluebelly, is a fairly well-known and recognized reptile. And it also seems to have captured the imagination of many northern California residents, as I found some of the most interesting information on this animal in Bay area publications.

Of the three common lizards found on More Mesa, the Western Fence Lizard, also called Bluebelly, is a fairly well-known and recognized reptile. And it also seems to have captured the imagination of many northern California residents, as I found some of the most interesting information on this animal in Bay area publications.

Stimulated by an increase in day length, Western Fence Lizards mate in the spring or early summer, and do not breed until the spring of their second

Stimulated by an increase in day length, Western Fence Lizards mate in the spring or early summer, and do not breed until the spring of their second

pulled off Western Fence Lizards … and there are a lot of ticks on the lizards … never seemed to carry Lyme. His conclusion was that the lizard’s blood had unique proteins that killed off the bacterium. Since the incidence of Lyme in California was markedly lower that incidence in the Northeast, where there are no Fence Lizards, the difference was awarded to the tiny Fence Lizard and it became a Super Hero.

pulled off Western Fence Lizards … and there are a lot of ticks on the lizards … never seemed to carry Lyme. His conclusion was that the lizard’s blood had unique proteins that killed off the bacterium. Since the incidence of Lyme in California was markedly lower that incidence in the Northeast, where there are no Fence Lizards, the difference was awarded to the tiny Fence Lizard and it became a Super Hero. What really is happening, and why, exactly, does the Northeast have 226 times more Lyme cases than we do in California? According to a recent article in

What really is happening, and why, exactly, does the Northeast have 226 times more Lyme cases than we do in California? According to a recent article in

In the beginning there were reeds and sedges

In the beginning there were reeds and sedges Bottom Line

Bottom Line

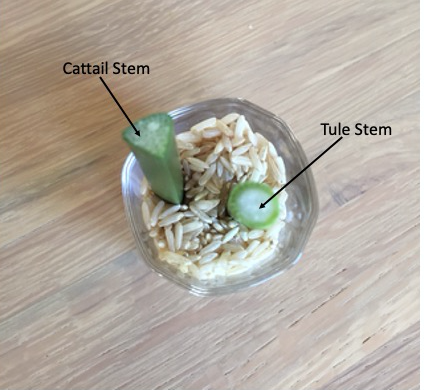

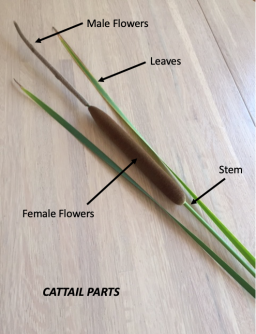

large diameter, brown, cylindrical female flower with a “fuzzy” appearance. This feature is responsible for the plant’s name and makes it easily identifiable as a “Cattail” … although it really looks more like a “corn dog!”

large diameter, brown, cylindrical female flower with a “fuzzy” appearance. This feature is responsible for the plant’s name and makes it easily identifiable as a “Cattail” … although it really looks more like a “corn dog!” Cattails are important to tiny fish, waterfowl and animals alike. Birds make use of these marshy plants for food and shelter, as well as a source for nesting material. During nesting season, one of my favorite birds, the Redwing Blackbird often makes its home in thick Cattail patches.

Cattails are important to tiny fish, waterfowl and animals alike. Birds make use of these marshy plants for food and shelter, as well as a source for nesting material. During nesting season, one of my favorite birds, the Redwing Blackbird often makes its home in thick Cattail patches.

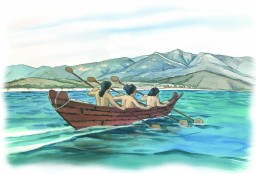

Tules: I’m guessing the whole “Bulrush” thing started with the story of “Moses in the Bulrushes”. However, this “baby in the river” tale is not unique to Moses. It may have originated in the legend of Romulus and Remus who were left in the Tiber, or that of Sumerian King Sargon I, who was abandoned in a caulked basket in the Euphrates.

Tules: I’m guessing the whole “Bulrush” thing started with the story of “Moses in the Bulrushes”. However, this “baby in the river” tale is not unique to Moses. It may have originated in the legend of Romulus and Remus who were left in the Tiber, or that of Sumerian King Sargon I, who was abandoned in a caulked basket in the Euphrates.

Prologue

Prologue

hikers deliberately kill Gopher Snakes because they are mistaken for Rattlesnakes. (As far as I know there has never been a report of a Rattlesnake on More Mesa.) Both species have similar coloration, markings and large heads. In addition, they are both known to hiss loudly, vibrate their tails and flatten their heads when threatened … a set of defense mechanisms designed to ward off potential predators. In the case of the Gopher Snake, this display is a type of mimicry, where they, a harmless species, mimic a harmful species … a Rattlesnake. However, while mimicry may be helpful in keeping predators away, it can cause problems for Gopher Snakes. Humans decide to kill them thinking they are venomous Rattlers. Instead, those who come upon a snake should take a quick look. A few ways to tell the two species apart is that Gopher Snakes are much longer and slimmer. Further, even though they can make a repetitive sound with their tails, they don’t have rattles. If it is obvious that the snake, whether it is a Rattler or a Gopher Snake, feels threatened, the wisest and most humane course of action is to simply go away. Once it figures out that it is not being threatened, the snake will also just go away.

hikers deliberately kill Gopher Snakes because they are mistaken for Rattlesnakes. (As far as I know there has never been a report of a Rattlesnake on More Mesa.) Both species have similar coloration, markings and large heads. In addition, they are both known to hiss loudly, vibrate their tails and flatten their heads when threatened … a set of defense mechanisms designed to ward off potential predators. In the case of the Gopher Snake, this display is a type of mimicry, where they, a harmless species, mimic a harmful species … a Rattlesnake. However, while mimicry may be helpful in keeping predators away, it can cause problems for Gopher Snakes. Humans decide to kill them thinking they are venomous Rattlers. Instead, those who come upon a snake should take a quick look. A few ways to tell the two species apart is that Gopher Snakes are much longer and slimmer. Further, even though they can make a repetitive sound with their tails, they don’t have rattles. If it is obvious that the snake, whether it is a Rattler or a Gopher Snake, feels threatened, the wisest and most humane course of action is to simply go away. Once it figures out that it is not being threatened, the snake will also just go away. There is no need to exterminate Gopher Snakes. These animals, while they can be intimidating because of their size and may look a bit like Rattlesnakes, represent no threat. Gopher Snakes are nonvenomous. However, if you provoke it, a Gopher Snake may bite and the bite may hurt. As for the big picture regarding venomous snakes in the United States, recent statistics show that five to six thousand people a year are bitten by them. Five of those people die because they did not seek medical care.

There is no need to exterminate Gopher Snakes. These animals, while they can be intimidating because of their size and may look a bit like Rattlesnakes, represent no threat. Gopher Snakes are nonvenomous. However, if you provoke it, a Gopher Snake may bite and the bite may hurt. As for the big picture regarding venomous snakes in the United States, recent statistics show that five to six thousand people a year are bitten by them. Five of those people die because they did not seek medical care. (This skin is in 2 pieces because I carried it in my jacket pocket to show More Mesa visitors and it received some rough treatment.) The shedding process is necessary to accommodate growth and to remove parasites on the old skin. Since the skin does not grow with the individual, as ours does, the snake has to do something entirely different. It starts by growing a new layer of skin under the old one. When the new layer is complete, the snake removes the old one. It’s just like taking off a sock. First it makes a small tear in the old skin, somewhere on the head area, by rubbing against something rough. Then it slithers out of the old skin and leaves it behind and it is usually inside out. Snakes shed their skin, on average, two to four times a year, varying with age and species. However, young snakes that are actively growing may shed every two weeks … compared to older snakes who may only shed twice a year.

(This skin is in 2 pieces because I carried it in my jacket pocket to show More Mesa visitors and it received some rough treatment.) The shedding process is necessary to accommodate growth and to remove parasites on the old skin. Since the skin does not grow with the individual, as ours does, the snake has to do something entirely different. It starts by growing a new layer of skin under the old one. When the new layer is complete, the snake removes the old one. It’s just like taking off a sock. First it makes a small tear in the old skin, somewhere on the head area, by rubbing against something rough. Then it slithers out of the old skin and leaves it behind and it is usually inside out. Snakes shed their skin, on average, two to four times a year, varying with age and species. However, young snakes that are actively growing may shed every two weeks … compared to older snakes who may only shed twice a year. When I started researching this Treasure Hunt, I was intrigued by why it is that humans are afraid of snakes. My first thought was to blame it on Adam and Eve. But it turns out, that it is in our nature to be afraid of snakes; that is, it is embedded in our DNA. Research over the past 10 years has given us some clues to the answer. In the beginning, early primates, and then humans, developed pattern recognition schemes for predators like lions, bears etc. But snakes don’t look like these kinds of predators … they look like sticks. Furthermore, they do not move like other predators … they slither. This would imply that the existing pattern recognition algorithms didn’t work. Then evolution took over, and humans who figured out they should fear snakes would have been at an advantage for both survival and reproduction. One clear indicator of this advantage was highlighted in a recent study. In that work, researchers found that both adults and children could detect images of snakes among a variety of non-threatening objects more quickly than they could pinpoint frogs, flowers or caterpillars. The implication is that we humans can identify snakes much more quickly than other things. This piece of our DNA is the reason that people who live in industrialized countries fear snakes … even when they have never ever seen one!

When I started researching this Treasure Hunt, I was intrigued by why it is that humans are afraid of snakes. My first thought was to blame it on Adam and Eve. But it turns out, that it is in our nature to be afraid of snakes; that is, it is embedded in our DNA. Research over the past 10 years has given us some clues to the answer. In the beginning, early primates, and then humans, developed pattern recognition schemes for predators like lions, bears etc. But snakes don’t look like these kinds of predators … they look like sticks. Furthermore, they do not move like other predators … they slither. This would imply that the existing pattern recognition algorithms didn’t work. Then evolution took over, and humans who figured out they should fear snakes would have been at an advantage for both survival and reproduction. One clear indicator of this advantage was highlighted in a recent study. In that work, researchers found that both adults and children could detect images of snakes among a variety of non-threatening objects more quickly than they could pinpoint frogs, flowers or caterpillars. The implication is that we humans can identify snakes much more quickly than other things. This piece of our DNA is the reason that people who live in industrialized countries fear snakes … even when they have never ever seen one!

Prologue

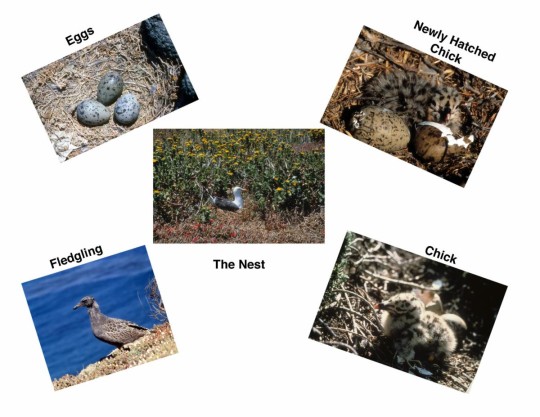

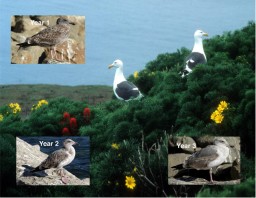

Prologue The Western Gull is a “four-year” bird; that is, it takes four years to reach adulthood and breeding status. The photo on the right shows the changes as the bird progresses to adulthood. It is easy to see that plumage varies and takes on more and more of the adult plumage characteristics in each successive year.

The Western Gull is a “four-year” bird; that is, it takes four years to reach adulthood and breeding status. The photo on the right shows the changes as the bird progresses to adulthood. It is easy to see that plumage varies and takes on more and more of the adult plumage characteristics in each successive year.