Living With the Lockdown – Treasure Hunt #23

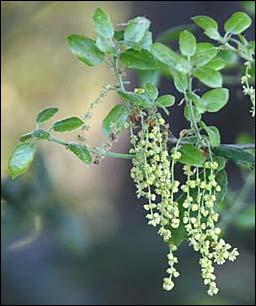

A Grove of Cottonwood is a Sight to Behold: Today’s treasure is native to the Western States, a member of the Willow family and closely related to Poplars and Aspen. It’s the Black Cottonwood. Deriving its name from a rough and dark colored bark, Black Cottonwood is one of the fastest growing trees in North…