Prologue

Prologue

Our Treasure Hunts usually end with some suggestions on where a treasure might be found. However, in this hunt, it’s incredibly easy! Western Gulls are all over town … the harbor, the beaches, Costco, McDonalds and every other place where food scraps can be easily appropriated … not that Western Gulls should be eating this kind of stuff! Read on to learn where Western Gulls can be found in a more natural habitat.

Western Gull, Big and Beautiful

The large, dark-backed Western Gull is found only on the Pacific Coast from Washington to Baja, and is seldom seen far from the ocean. This distribution is very limited compared to most North American gulls, and since we are on the ocean, Western Gulls are all over Santa Barbara.

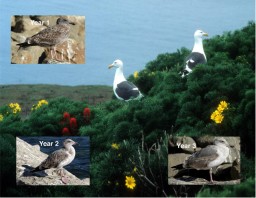

The Western Gull is a “four-year” bird; that is, it takes four years to reach adulthood and breeding status. The photo on the right shows the changes as the bird progresses to adulthood. It is easy to see that plumage varies and takes on more and more of the adult plumage characteristics in each successive year.

The Western Gull is a “four-year” bird; that is, it takes four years to reach adulthood and breeding status. The photo on the right shows the changes as the bird progresses to adulthood. It is easy to see that plumage varies and takes on more and more of the adult plumage characteristics in each successive year.

Most of the Western Gulls we encounter here in town are full-grown adults … bold, raucous and fearless around humans. But when the adults are not dining on French fries and other human food, they (and the juveniles) are at sea consuming all manner of aquatic life including fish, shell fish, eggs and young of other birds and what they can scavenge around sea lion colonies. And they, like many other sea birds, are clever thieves … stealing food from other sea birds. In short, they are very “opportunistic feeders”.

Once Again … Procreation

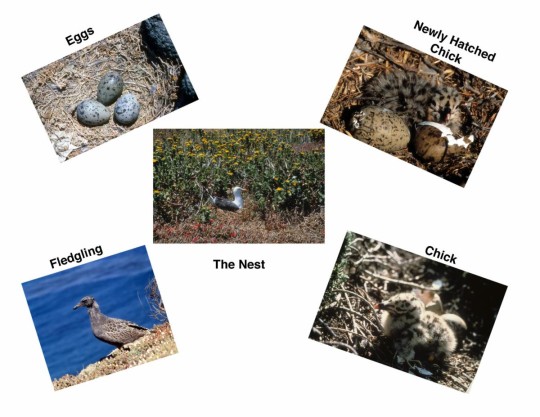

While the photo above shows the progression to full adult size and plumage, the whole process starts with the nesting period and the chicks. The chicks are cute and it is … after all … Spring. Western Gulls nest in colonies on off shore islands, rocks and on islands inside estuaries. We are especially blessed because of our proximity to the Channel Islands, where large colonies are found on both Santa Barbara Island, with 7,000 nesting pairs, and on Anacapa Island, with 10,000 nesting pairs. The modest nests are built on the ground by finding a depression and filling it with vegetation, feathers and whatever else is available. Several, but most often 3 eggs, are laid.

These grayish eggs … with dark “polka dot” spots, are incubated, by both the male and the female, for about a month. At that time, the chick will hatch with the aid of a small projection at the end of its beak. This projection, or “egg tooth”, has two jobs to do. First, it breaks the sac surrounding the chick inside the egg allowing the nearly born chick to access oxygen stored between the sac and the shell. When that is done, the youngster now has enough oxygen to tackle the second, and more difficult task … to crack the shell and emerge. With its work done, the egg tooth falls off when the chick is 2-3 days old.

Mom and Dad Have Big Jobs

Feeding

In the above photos you can see that the newborn looks like a down covered version of the

egg … grayish with the same blackish “polka dots”. And it needs to be fed … for up to three months! Like humans who are attuned to the vocalizations and fussiness of their offspring when they are hungry, the Western Gull, like many other gulls, has the ability to recognize the needs of their offspring as well. When the chick is hungry, it signals by touching a red dot on the lower jaw of an adult, who will then regurgitate a meal for the hungry chick. Further, the color red, is programmed into the DNA of the gulls, so no other color spot will do. This conclusion was such a scientific breakthrough, that fifty years ago the research on this signaling approach won a noble prize for the Dutch biologist Niko Tinbergen.

Teaching

Just like we have to teach our kids to walk and drive a car, adult gulls must teach their offspring to fly. The downy birth coat will soon be replaced by feathers, and the fledgling will be able to fly after 6-7 weeks. These flying lessons are relatively risk free when the nest is on the ground. The fledgling can only crash and fall a few soft and vegetated feet. However, I once observed an adult pair who had chosen a very safe nest location in a small crevasse on a high cliff. With many loud vocalizations, they had urged the youngster to the edge and then squawked their instructions to fly. The fledgling approached the edge, looked down the cliff face to the ocean hundreds of feet below, turned toward its parents, and gave them a look that clearly stated “You gotta be kidding!” Then it hustled back to the nest. I watched this attempted flying lesson repeated over and over until the boat had to leave. I’m sure the kid eventually “got it” and I smiled all the way back to the harbor.

Why have I spent so much time on this part of the gull life cycle? Because it is happening as I write … a three week period when you will see nothing like it without traveling to far distant places around the globe. In a non-pandemic year, I would be on a boat to Anacapa Island to look at the thousands of nests, adults and chicks! It is an incredible sight and one that happens right here in our very own back yard.

And Up North …

The numbers of Western Gulls in the Bay area are dwindling because their natural food supply is not as reliable as it has been in the past. And scavenging has also become more difficult. Gulls and other birds have historically used dump sites to scavenge for discarded (and unhealthy) human food remains. To discourage this practice, these areas are now deliberately being covered over more rapidly than they were in the past.

As a result, Western gulls have become a serious nuisance for baseball parks in the Bay area. For 20 years, both the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland Athletics have had thousands of gulls flying over both Oracle Park and the Oakland Coliseum. Originally, they came after the game was over, but they are now arriving as early as the 7th inning. They swarm the field, pooping on fans, making loud raucous noises, and distracting the players. When the games are over, they dine on leftovers of stadium food discarded in the stands … with a definite penchant for nachos and garlic fries.

How do the birds know when games are about to end? Nobody knows! About ten years ago the gulls made a hasty exit from the San Francisco stadium when a Red-tailed Hawk showed up. But the hawk decided it did not particularly like the neighborhood and left. Back came the gulls in full force. A falconer is one answer, and the Oakland stadium has done just that … but it is extremely expensive. Oracle Park also tried to lure a pair of Peregrine Falcons into making the stadium its permanent home, but that effort failed. Several other attempts at making kites that looked like raptors also failed. As far as I know, the ritual invasion of the Western Gulls is still going on. Makes one wonder if perhaps this brand of scavenging might not be so fruitful if humans properly disposed of their own food trash?

Most of the photos in this Treasure Hunt were taken by Donley Olson and Larry Jon Friesen. The baseball photo was from the Mercury News in San Jose.

There are Trees…and Then There are “Trees”

There are Trees…and Then There are “Trees”

The Whole Story

The Whole Story

Some invasive plants move from their home territories via stealth. They hitchhike on boots, backpacks, clothing, packaging containers and ship bottoms. But, by in large, most were purposely transported from their homeland by humans who thought they were treasures that would be valuable in other, far-away places.

Some invasive plants move from their home territories via stealth. They hitchhike on boots, backpacks, clothing, packaging containers and ship bottoms. But, by in large, most were purposely transported from their homeland by humans who thought they were treasures that would be valuable in other, far-away places.

This treasure, also known as salt cedar, is a shrub or small tree originally from Eurasia and Africa. It took root, literally and figuratively, about 200 years ago…and did so with the blessing of the federal government. After importation, it was sometimes used as an ornamental or as a windbreak.

This treasure, also known as salt cedar, is a shrub or small tree originally from Eurasia and Africa. It took root, literally and figuratively, about 200 years ago…and did so with the blessing of the federal government. After importation, it was sometimes used as an ornamental or as a windbreak.

First the Birds, then the Bees and now … the Butterflies

First the Birds, then the Bees and now … the Butterflies

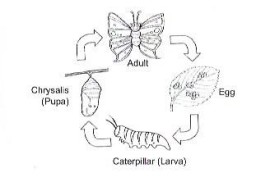

Eggs begin a new cycle and are laid on plants that the caterpillar likes to eat … and the caterpillar is usually a very picky eater!

Eggs begin a new cycle and are laid on plants that the caterpillar likes to eat … and the caterpillar is usually a very picky eater!

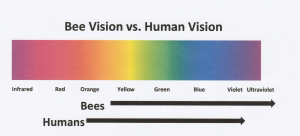

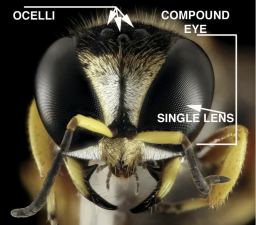

Vision is accomplished using two very large compound eyes. These eyes are amazing examples of nature’s engineering. A bee compound eye is made up of thousands of tiny lenses called facets. Each of these facets takes in one small part of the insect’s field of view. The bee’s brain then converts these signals into a mosaic-like picture made of each image. Some bees have up to 8,600 facets.

Vision is accomplished using two very large compound eyes. These eyes are amazing examples of nature’s engineering. A bee compound eye is made up of thousands of tiny lenses called facets. Each of these facets takes in one small part of the insect’s field of view. The bee’s brain then converts these signals into a mosaic-like picture made of each image. Some bees have up to 8,600 facets.